Wolfgang Tillmans

The particularities of the artist who makes the ordinary extraordinary

For nearly 20 years now, Wolfgang Tillmans has brought new meaning to photography, and to the way images are displayed and understood. Born in Germany and based mainly in London, Wolfgang creates a community around him with his graciousness and his curiosity, characteristics that both play a vital role in his work. The first photographer to win the Turner Prize, Wolfgang never questions the veracity of the medium but uses it to find truth in art itself. On the eve of a major Tillmans exhibition in London, Fantastic Man’s reporter travels with the artist between London, Berlin and New York, to see just how much of the man it takes to make the picture.

From Fantastic Man n° 11 — 2010

Text by PAUL FLYNN

Photography by ALASDAIR MCLELLAN

LONDON

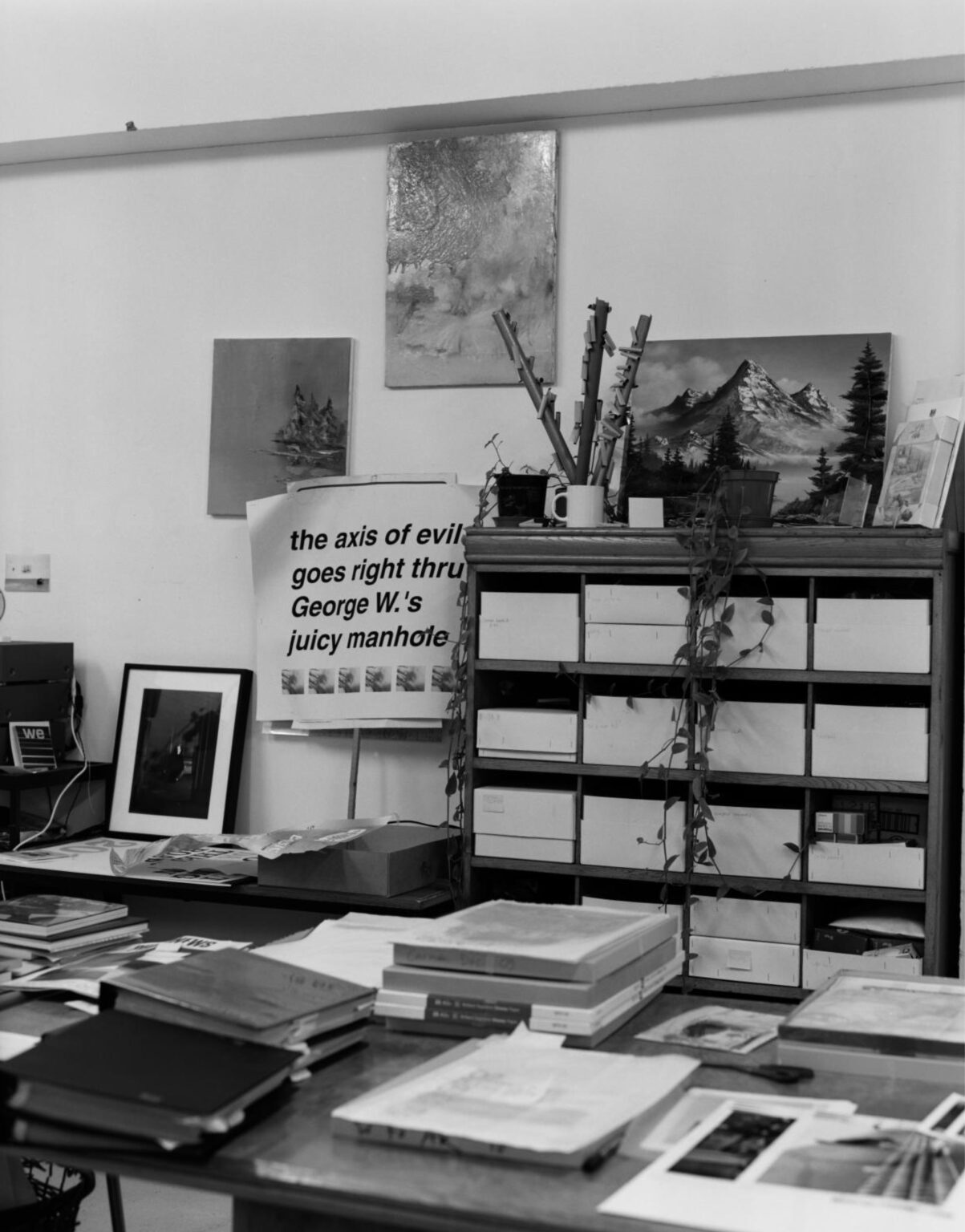

Wolfgang Tillmans sits in his workspace in east London. It is Saturday evening, and he has already spent several days contemplating a scale model of an exhibition of his work that is to open in New York in three weeks’ time. It will be his first US show in a year and a half. At some point during the two hours we spend together in the studio, he casually asserts that I will be granted access to anything and everything I’d like to see him do in the run-up to the show, whether in London, Berlin or New York.

The scale model of the exhibition fits onto half a trestle table and stands some 30cm high. Small versions of the pictures are delicately taped to the thick, white cardboard walls. The real pictures are taped around his studio, a 300-square-metre industrial unit in a rare pocket of east London that has yet to show any surface signs of gentrification.

The studio looks like it could be one of his pictures. “Aha,” he says, “that is funny. What you see is a still life; what I see is a bunch of flowers for the studio.”

Wolfgang is tall, with sympathetic eyes and a huge smile. His German accent is heavy, despite 20 years living in London, and his vocabulary is immaculate. When he smiles, his face works in almost comic slow motion, his whole head rising with his lips. He is a committed pacifist with a fetish for army-wear, the irony of which he is all too aware. He is a gentle man.

Wolfgang had intended to take 2009 off, but his plans not to exhibit for at least a year were interrupted by a request to show at the Venice Biennale. He nevertheless managed to fit in some travelling with his boyfriend, the artist Anders Clausen. They travelled to the Far East for the first time, to China and Thailand, with an unintentional stop-off in Dubai on the way back. “Have you been there?” he asks. “Awful.”

Throughout the period that was meant to be a holiday he could not ignore his artistic impulse. Hanging on the wall is a picture of the mirrored ceiling at a nightclub in Venice, taken at an unusual angle. “Awful,” he says again, of the club, not the picture. “But I have to be careful that the work does not descend into kitsch or condescension.” He mentions the photographs of Martin Parr – “I don’t want to be mean to him; what he does he does very well” – as a negative benchmark by which artistic levels of kitsch can be gauged.

The new exhibition is a deliberate U-turn for Wolfgang. It will feature none of the abstraction that he had introduced to his work in 1998, and will continue his earlier practice of hanging the work, unframed, with tape, nails and bulldog clips. The most significant move forward with the coming exhibition will be its international feel, away from the artist’s familiar territories of east London and Berlin. The scale model includes a picture of a man bathing in the Ganges (Wolfgang has deliberated long and hard whether to include it), and a shot of a Shanghai skyscraper, alongside several more homespun and immediately recognisable still lifes with textiles, mostly his own clothing.

Wolfgang is now 41. Throughout all his work, from his first international solo show in 1993 to winning the Turner Prize in 2000, and beyond, there is the sense of a single underlying question: what makes a picture? That question is still noticeably present in the work to be shown in the New York exhibition. One picture is of a sheet of glass being transported in a factory. Another features glossy gossip magazines on a shelf. There is a still life of a rain drop on an orchid that Wolfgang took in Thailand. “I mean, this could almost be the cover of a menu in a restaurant,” he says, pointing to it. With tricky subject matter, there is always a delicacy and often an idiosyncrasy to Wolfgang’s eye that belongs only to him. With every picture he takes, he asks himself: what is it that I am attracted to here?

Wolfgang is contemplating which picture visitors to the gallery should see first. At the moment, taped to the cardboard wall in the entrance foyer of the scale model is a large picture of a baby in the car seat of a very suburban car. It is titled Roy. “It is so not what you would expect of me,” he says, staring intently at the image. I slowly begin to carousel with Wolfgang’s manner. He is certainly one of the most thoughtful men I have ever spent long periods of time with, though he can also punctuate the patience of his purpose with quick, sprightly decisions. I find him almost mystically serene.

In the picture of the baby, a reversed tax disc sticker is visible on the window of the car. Because of the font used, when reversed, the year 2009 printed on the sticker appears to spell out the word “poof”. He responds immediately and kindly to any observation of his work and laughs gently at this one. “But this is the reality of how many people live their lives,” he says, pointing at the picture without judgement.

Wolfgang’s studio is just a few footsteps away from the gallery of his London dealer, Maureen Paley. It used to be an umbrella factory, and when bidding for the lease of the building just before his Turner Prize win, he was competing with a group of local African churches who wanted to turn the space into a place of weekly worship. He says that his Indian landlord shows no sign of being impressed by what he does. “He has never commented on any of the photos, for example.” Wolfgang’s artwork is everywhere in the studio. “He only cares about whether the rent is paid on time.” It always is.

For the past few years, Wolfgang has also used the studio for his own summer parties which have become the stuff of local legend. These parties are a direct reflection of Wolfgang’s world. The mythical boundaries between the sometimes very separate worlds of art, fashion, music and nightlife collapse within the confines of his studio. Because he is an inclusive person, his parties are, too. They are cool in a liberal usage of the word, as in the opposite of uptight.

These parties cut deeper, too. They are part of his ongoing, egalitarian interaction with the world. “It’s fun to give something that you also get so much back from. It’s very interesting to occupy my mind with something outside of myself. Even though I deal with the outside world with my camera, it is still dealing with my own stuff, day in, day out. I find the parties a very refreshing thing to do for my mental agility.”

Wolfgang does not throw his summer parties as a launch, or to coincide with an exhibition, but simply for the sake of having a party. “It’s good to think about something that isn’t just furthering my own direct interests, and I put a lot of time and effort into them. They are not truly altruistic. They are altruistic because they can be. I am aware that a lot of people don’t have the space or the money to do that. As someone who is fortunate enough not to have to just survive, it’s good to utilise my resources. I don’t have any particular lifestyle needs.”

In a week, Wolfgang will visit Berlin, where he will replace some art he has hanging in the Panoramabar, part of Berghain, probably the most influential club in the world right now. “There is a lot of bad art involved in clubbing. I don’t think that art necessarily lends itself to many applications. The moment it serves a function, it is not purposeless, yet I think purposelessness is quite crucial to art. Otherwise it is an illustration. In the Panoramabar they have just the right understanding. They are making a mad place, but they are also very realistic about it. It is a reasonable undertaking to have a great techno club with a sex club attached to it, architecturally. Then sometimes the whole place becomes a sex club and the closed-off area has theme parties. It’s so caring for the human mind and the different receptors of what people might want, to offer this playground paired with an aesthetic sense that has never been trashy.”

BERLIN

Wolfgang’s studio in Berlin is in a building that was designed by Max Taut, the less famous brother of Bauhaus architect Bruno Taut. Wim Wenders once occupied the top floor and Nina Hagen’s manager operated out of a studio here when Wolfgang first moved in. The stairwell was prominently featured in a film by the avant-garde filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger. At 680 square metres, the studio is twice the size of his London space.

Wolfgang is very precise about certain aspects of his working conditions. For example, he is most specific about the weight of lead in the pencils that he uses to sign his art. His pencil of preference is by the Austrian brand Cretacolor. He uses their 7B graphite. Its marks, he notes, are heavier than those of 8B pencil leads from other brands, yet the Cretacolor 7B pencil has the satisfying performance aspect of leaving no indenture on photographic paper, a carelessness that other pencil factories may wish to correct.

All this could lead the reader to believe, incorrectly, that Wolfgang is a fussy man. There is no doubting that he is incredibly particular. But his particularities are ones that are easy to warm to, and that are mostly deployed in the service of his work. Some aren’t. He never smokes a cigarette before 6pm, for example. Whenever I am with him, at some point between 6.05 and 6.25pm a rogue, unopened packet of Marlboro Lights will appear close by. While there is a satisfying certainty about entering and re-entering his world, one can never be certain of where the day, or more specifically the night, will end.

While roaming around the studio I notice a recent family portrait showing Wolfgang with his sister, Barbara Forkel, 44, and brother, Christian Tillmans, 46, all smiling in the family kitchen. He thinks it must have been taken by his father, Karla A. Tillmans, now 79. His mother, Elisabeth Tillmans, is 72.

Wolfgang was born in the small town of Remscheid, Germany, in 1968. He moved first to Hamburg at the end of the ’80s and then, for a few weeks during the crazy acid-house summer of 1989, to Berlin. From 1990, after having read in an interview that the fashion photographer Nick Knight had attended the Bournemouth School of Art and Design, Wolfgang spent two years studying photography in the incongruously-sleepy British seaside town of Bournemouth. He loved it. “People always laugh, but I had a great longing for the English seaside. Rainy, sad, autumnal…falling in love and spending time on the pier. I was happy to be in a provincial place and I relished the local gay disco, The Triangle. The other foreign students couldn’t wait to go to London for the weekend. But I moved to Britain because I had an affection for English culture.” Since 1992, Wolfgang has lived mostly in London, with a gap of two years in the mid ’90s, when he lived in New York.

It is lunchtime, and there is another scale model of the upcoming New York exhibition at the far end of the studio. Wolfgang’s German assistant, Carmen Brunner, presents him with a series of postcards of his own work, from which he must choose an image to send to the building’s caretaker. “What is the celebration? Christmas? New Year? Maybe just ‘Thanks for your help’,” he says, before spending a full 20 minutes deciding on a tone that is appropriate for a man whose first name he does not know and whom he refers to only as Neuendorf. He says that it is not unusual in Germany to call another man by his surname, nor is it considered impolite or overly formal. Wolfgang says that as a professor of interdisciplinary art at the Städel-schule in Frankfurt, he is sometimes referred to as Professor Tillmans.

In the late afternoon, we stroll in the sub-zero temperature between distinct aspects of Wolfgang Tillmans’ Berlin. He spends 15 minutes at his framers’ shop in serious discussion about a particular type of rivet. Afterwards we catch a cab to the Panoramabar to oversee the lighting and hanging of his art. His feelings towards the nightclub are affectionate and sincere. He was last in the Panoramabar for New Year’s Eve, where he observed and participated in a 36-hour party and noticed a man napping, mid afternoon, on a banquette with the music, lights and detritus of the nightlife pulsing around him.

The Panoramabar and Berghain were founded five years ago, metamorphosing from the lawless club Ostgut. For the opening, Wolfgang installed in the Panoramabar two abstract images and a portrait of a vagina. The new pictures are two enormous abstract paintings with light and a visceral but oddly poetic portrait of the backside of a man bent over, revealing his open anus. “It is the last taboo,” he says.

In 1998, Wolfgang began experimenting in the darkroom with exposure and light, moving away from photography into something less certain. He showed his first set of abstracts in 1998, a series of 60 prints titled Parkett Edition, dated 1992–1998. It was a radical and significant shift in his art, away from his signature ability to find the extraordinary in the ordinary through his camera. The abstractions moved his art into a whole new realm of visual language. He began his ongoing series of “paper drop studies” in 2001. “The name came from the hanging and falling shape of the first ones,” he says. “Only in 2005 did I start the horizontal type where the paper actually resembles a drop shape. So the title became a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

When he presented the three new art works to be hung in the Panoramabar, its owners, Norbert Thormann and Michael Teufele, unfettered libertines, responded with the words “The arsehole is perfect!”

While we are still in the nightclub, just after 6pm, Wolfgang smokes a cigarette. We dine that night at a corner restaurant called the Oppenheimer Café and we talk almost immediately about being from a generation of gay men that grew up in the ’80s under the morbid suspicion that one’s sexuality might also result in one’s death, and what a curiously unsettling perspective that afforded youths. For extended periods of time during his teen years, Wolfgang would sit in his bedroom just being angry, listening only to Joy Division. Some of his pictures of cloth and worn clothes have mistakenly been associated with the idea of loss and emptiness, and as a comment on AIDS. In fact, the opposite is true. Wolfgang likes the association with bodies, the intimacy of clothing just shed.

Over dinner he says, “My ultimate, ultimate truth is that ultimately I don’t know. People pretend that they do. My fundamental understanding is that I might always be wrong. I may be assured or confident, but I could always be wrong. I think that’s probably one of my biggest strengths, that I don’t fear failing. Or that I know that the fear of failing is a huge inhibitor. So many people don’t achieve what they want to achieve because they are too precious about losing face in the short term. And so, for example, with photography as a medium, you have to be embarrassed sometimes. When you ask someone to sit for you, that moment always includes the potential for rejection. If you can’t handle rejection or you just want to avoid rejection at all costs, you are not taking the risks that make good pictures.”

He recounts two stories about early personal failures and humiliations. In the first he is 13 years old, volunteering to give a talk at a local fair about his first obsession: astronomy. Wolfgang had just learnt about stars and believed himself to be equipped to talk on the subject. When it came time to give his talk, his projector failed and he couldn’t speak; he left the stage acutely embarrassed. The second took place at college in Bournemouth. In an attempt to nourish one of his early ambitions of becoming a rock star – “more of a Marc Almond-type synth star, actually” – he offered to be the singer in a band at the graduation ball for the class ahead of his, only to find out on the night that he could not sing in time or in tune. “These incidents vaccinated me against failure. As a 19-year-old, having just done my A levels, I moved to a big city, Hamburg, and within a few months I approached a respectable artists’ cafe, the Gnosa, about showing my work there. To make these photocopies and to really believe this is art was wonderful… It could’ve been equally embarrassing if they had been bad. It probably seemed a little mad to people that I had this drive and this belief that the work was good and that it mattered. And that somehow if this mattered to me, there might be some relevance in it to the outside world.”

After dinner we return to the studio. Wolfgang studies the scale model of the New York exhibition for another three-quarters of an hour. He is still somehow perturbed by Roy, the picture of the baby in the car seat. “What is it now? Have I only just discovered babies? Parenting?” He blanches at the idea. “There is always a disconnect for me with straight men. I never feel the same. I think there is a fundamental difference. It’s almost like there are men and women and then there are gays. I don’t believe so much in just a gradual ‘Oh, we’re all just different shades of grey.’ I think there is something that I have felt from very early on that is very different from the straight world that I grew up in.”

He replaces the baby picture with a shot of a group of motorcyclists standing on a Berlin street, in full, garish and slightly ghastly techno leathers. He turns to me after he has made the switch. “You liked the baby,” he says. I say nothing. It is past midnight.

LONDON

Back in his London studio, Professor Wolfgang Tillmans offers an academic-sounding theory of success: “I hadn’t necessarily predicted my success, but it has never surprised me and it always seems to come at the right time. I have always felt a sense of purpose, that I had something to say and that I wanted to say it. That if in a certain phase I believed in something very deeply, then there might be 50 per cent of the population that might possibly relate to that. And if only five per cent actually do relate to that, well, that is a lot. One usually thinks of success or fame in a 100 per cent kind of way but that is not at all right. It’s quite amazing if you even manage to speak to one per cent. Speaking to five per cent does not seem like hubris. You must always remember that “Being Boring” was only ever number 20 in the charts and that “Blue Monday” was only number eight in the charts; there were seven songs that were deemed more successful at the time. If you can really touch a small number of people, I think that that is a more meaningful success than being one of the three or four artists that are in the press all the time. In the last ten years or so I have dropped out of that, because it’s so uninteresting. I have become less and less interested in the idea of mainstream success. It comes at a cost: you also have to compromise on the art side. What is talked about in the Evening Standard is maybe not what is considered really important in other places. That kind of success requires upkeep and maintenance. Winning the Turner Prize is one of the few experiences where an artist gets close to feeling famous in a real-world sense, rather than an art-world sense. In the days after I won the Turner Prize it was slightly unreal how people would discuss my work.”

The day after Wolfgang won the prize in October 2000, the Daily Telegraph headline ran: “Gay Porn Photographer Snaps up Turner Prize”, predating by a full four years the Daily Express headline: “Booker Won By Gay Sex”, in reference to Alan Hollinghurst’s victory for his novel ‘The Line of Beauty’.

Wolfgang remembers that the public reaction to his win was more sensitive. “The day after I won the prize, I stepped out of the house and a cyclist drove past shouting, ‘Congratulations’. Then the newspaper agent knew me and suddenly I was literally recognisable in the street. People would stop me and say they had seen me on TV last night. Within seven days it had diminished to a quarter of the number of people saying it and within a month it had gone back to the five per cent. I realised that in order to be famous you probably have to be in the media three times a week on a continuous basis. There was no reason to continue that. There was nothing driving it. That whole experience happened once, I never asked for it again and it somehow drifted away.”

This summer, Wolfgang has a major exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London. He last showed in his adoptive hometown at Maureen Paley in 2008. “After the last show I had with Maureen, there was a piece in a newspaper saying that I was making a comeback. In the previous eight years I had had ten major museum shows around the world. So the hours that I put into the show in New York or into whatever I do are always for the very small audience that I imagine. I almost have a handful of people in mind that I am doing this show for.”

It is important to Wolfgang that his confidence in his success not be mistaken for certainty – about anything. “My work is about doubt,” he repeats. “I think that’s really where it is at. The people that I feel touched by or care about or who interest me usually have an inherent sense of doubt and uncertainty about who they are and what the world is. They have retained a kind of flexibility in their head, not shutting down but being open about their fears and uncertainties. Even though of course I might come across as self-assured, I fear nothing more than losing a sense of uncertainty and doubt about myself. I am really most mindful of that. The moments where I recognise that I have lost track of that are moments of real tragedy for me.”

NEW YORK

It is Friday, the day before the exhibition opens, and Wolfgang arrives at the gallery of his New York dealer, Andrea Rosen, at 11am. Tuesday he had been at the gallery till 4am, Wednesday until 5am, and yesterday until 1am, giving himself a break to attend one of the regular parties held by the photographer Ryan McGinley in Chinatown. He is a little hungover; nothing that a power-nap at 7pm won’t solve.

He is clearly loved by the gallery staff, not just for his art, but for who he is. “It’s the exhibition that you always look forward to,” says Rosen’s right-hand woman, Bronwen. Wolfgang says that he always assumes people are on the same side, a surprisingly rare attitude in artists from any medium. The tenderness of his art, even when the subject matter is profane, comes directly out of the behaviour of the artist.

It is only when faced with the reality of the gallery that I understand the significance of the scale models and the hours spent in preparation for the show. Wolfgang has spent three days and nights taping to the wall the exact final cut of the exhibition, and now two technical staff at the gallery are helping him with the precise measurements for taping the pictures to the wall.

I watch Wolfgang’s body contort into unusual shapes as he unravels pictures from a stepladder. He almost becomes one with them, copying the paper’s curve with his spine as the image is slowly revealed. He instructs the men in the studio to hold the photos only by the corners, between their forefingers and thumbs. The tape he uses to hang his pictures is made by TESA, a Swiss brand he imports especially. Theirs are the only tape dispensers without serrated blades; they create a clean, finite cut.

When he started exhibiting, there were two major misconceptions about Wolfgang’s work. “People thought it was a grungy gesture to tape them up,” he says, adding categorically: “It was not.” The other was that because there was an intense air of reality to them, they were simple snapshots. In fact, his work has always been a mix of the staged and the unstaged.

When he notices diagonal lines across two adjacent pictures, he questions their positions next to one another. Andrea Rosen is with him. “I don’t think that people looking at your work think you make these formal decisions,” she says. As small but intricate changes happen to the structure of the show during the day, Andrea is displaying some half-comic concern about a still life of faeces in grass, called Scheisse, hung at knee level.

Andrea has been Wolfgang’s East Coast US dealer since 1993, when she and two other prominent New York interests courted the artist. She was first alerted to his work after receiving an invitation to his second solo show in Cologne. The picture on the invite was one of Wolfgang’s most immediately eye-catching and iconic gifts to the contemporary art culture: Alex in the Trees. It was enough for Andrea to board a plane to Germany and then follow the artist to his home in London, eventually winning his trust.

Now, in the foyer of her gallery, the baby in the car seat is back as the first picture of the show. On a right-hand wall of the foyer is the only framed piece in the exhibition, showing the decadent nighttime at Ostgut, intertwined with pictures from churches. It is called Ostgut December Edit. “They were made in a very intense and passionate time of my life,” he says.

Early in his career, Wolfgang had distinguished himself from the then vogue-ish Brit Art conglomerate by choosing specific mediums other than art galleries to display his art. Because some of his work appeared in style magazines, most particularly in i-D, he was mistaken by the British art media as a jobbing portrait and club photographer. The major art territories of Paris, Cologne and New York had no problem with his work appearing in magazines, as it occasionally still does.

Some of Wplfgang’s New York collectors insist on seeing the new show before the public opening the next day. There is mention of Mario Testino popping by before he leaves the city. A gentle conga line of interested parties interrupts the afternoon’s hanging, and Wolfgang talks each one through the show. With each interested party he is patient, attentive and affects a pleasantly passive position. There is a fascinating intimacy to this exchange between artist and collector. Everything up to the point of sale is foreplay, on both sides, prior to the satisfying union of passing a piece of art from the creator to its new home.

At one point the traffic in the gallery heats up as an art consultant arrives with her client and a small child, perhaps five years old. But suddenly the client has to leave, as her husband is trapped in the restroom of his favourite restaurant. “Have they called the fire department, even?” she asks when he calls her on the phone. Another collector is an impressive man with a booming voice, a side-parting in his hair and heavy-framed spectacles, who is sitting in Andrea’s office at the back of the gallery and telling Wolfgang enthusiastically what he likes about the latter’s work. “You see the whole world,” he says, his voice amplifying with every statement. “Vice, technology, sex, nature. It’s about everything spinning in front of your eyes. The thing is, in this world, everything is spinning out of control. There is a madness to the whole world. You are capturing the madness of this world.”

At 4.45pm, the singer Michael Stipe arrives with his boyfriend, the photographer Thomas Dozol, and Stipe kneels involuntarily prostrate in front of the picture of the techno bikers, which is now positioned in the second room. Dozol takes his portrait from behind. Stipe wows openly at the exhibition. “It is deep. It is moving, which people need right now.” A pause. “By the way, Andrea told me not to tell you that she told me to tell you to lose the poop.” The first sale is made at 5.14pm to the man who was trapped in the toilet.

When sleeving some of his work in the suite of offices at the rear of the gallery, Cretacolor 7B pencil in hand, Wolfgang notes that no one who has seen the exhibition seems to have found any of it funny yet. “Look, Wolfie,” says Tamsen, one of Andrea’s staff, “I am not going to stand in front of one of your pictures and start laughing, and then find out that it is the one you consider to be the most meaningful in the exhibition.” The staff at the gallery adore him. All the women call him Wolfie. As an aside, Wolfgang notices the distinction between the male and female members of staff at Andrea Rosen. All the men, bar one, are engaged in manual labour and technical activities; the women are all at desks.

When I ask him later about his relationship with his own masculinity, he says, “It of course depends on what one sees in the word masculine.” And then: “I don’t want the work to be hard. I can play with hardness and I like to play with images of hardness and masculinity and dress, but I never want to be hard. You know I see myself as gentle, which isn’t in contradiction with masculinity.”

There is a light interchange between the artist and some of the staff as they prepare to leave. When Wolfgang asks Andrea, “Are you going to wear your brown leather catsuit tomorrow?” his mouth and head upturn into one of his great smiles. She flips back, “I promise you I’ll fit into it by the Serpentine,” referring to his forthcoming London show. Wolfgang will not leave the gallery until 4am.

It is 1pm on Saturday, five hours before the opening of his show, and I meet Wolfgang in the lobby of his hotel. He is wearing an Everlast tracksuit top, jeans and trainers, and has clipped his own hair. He asks if the line around his head is even. It is. “Oh, super.” “Oh, super” seems to be something of a catchphrase for the artist. In the time we’ve spent together, I’ve often heard this casual affirmation.

We wander around art galleries, starting at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in Greenwich Village, where the artist Silke Otto Knapp, whom Wolfgang knows, has a new collection of watercolours on display. Walking into an art gallery with an important artist presents its own peculiar dynamic. In every space we enter there is a sly little confirming nod from the receptionist. Someone always wants to speak to him. Because his disposition is kind and interested and he sets up the tone of his conversation in this way, he almost forces the people he happens upon to respect the pleasantry. In company, Wolfgang possesses the quite incredible natural duality of having the impeccably good manners of a shy person while not being remotely shy.

At Reena Spaulding’s Fine Art in the East Village, a woman cannot believe that he could be so casual as to stroll around galleries on the afternoon of his opening, as if perhaps he should be sat in the empty gallery, fretting. “I am unusual among artists,” he tells me, “in that I like other people’s art. I am interested in it.”

At his own opening, what Wolfgang calls his “grin muscles” are lively and active. He is a diligent if unassuming host. He takes a glass of champagne with the gallery staff at 5.45pm and by 6.15 the trickle of excitable patrons has turned into a full gallery of admirers despite it being the coldest night of a biting New York winter. The attendees of a Wolfgang Tillmans gallery opening in New York are an interesting mix of downtown and up. Wolfgang refers to the opening as like being caught in the frame of a Woody Allen movie. A succession of erudite New Yorkers offer their verbal applause.

If an opening is the direct reflection of the artist it celebrates, he should be thrilled with his. Boys in anoraks and outsized boots, wearing an air of concerted deliberation and occasional restlessness, rub shoulders with prominent art-world powerbrokers from MoMA. The age, race and gender mix is impossible to pinpoint. At one point John Waters turns up and blends seamlessly into the evening’s demographic.

The opening is followed by a dinner at Indochine, a restaurant with particular significance for both Wolfgang and Andrea. When Wolfgang used to come over to see Andrea in the early days of his international career, she would take him to dine at the Astor Place Restaurant, which was an old Warhol favourite just prior to his death. As well as marking Wolfgang’s opening, the meal is also to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Andrea’s gallery.

The dinner progresses from the civilised to the raucous the more the wine flows. I sit between two of Wolfgang’s collectors, one who owns two popes by Francis Bacon, and another who has just bought 25,000 square metres of real estate upstate, where he intends to set up an art foundation. Wolfgang begins the night seated at our table. The collectors are amicable men, passionate about modern art, a lawyer and an MD, simultaneously able to crumble and affirm the fabulosity of the New York art set.

Between them, Wolfgang and Andrea manage an effortless waltz amongst the diners. At certain moments you can see them beaming at one another, her with her immaculate New York finesse, him with his inviting Northern European bluffness.

I ask the collector seated directly opposite me whether he liked Wolfgang’s new show.

“Yes, there is important work there,” he responds.

Were there any pictures that he considered particularly important?

“Yes. The baby in the car seat when you just walk in.”

I find Wolfgang Tillmans at 1am, sitting on someone’s knee, drunk and laughing. He will go on to The Boiler Room, an East Village gay bar, and only leave there at 3am.

“Not a very late night,” he later says.