Popular Culture

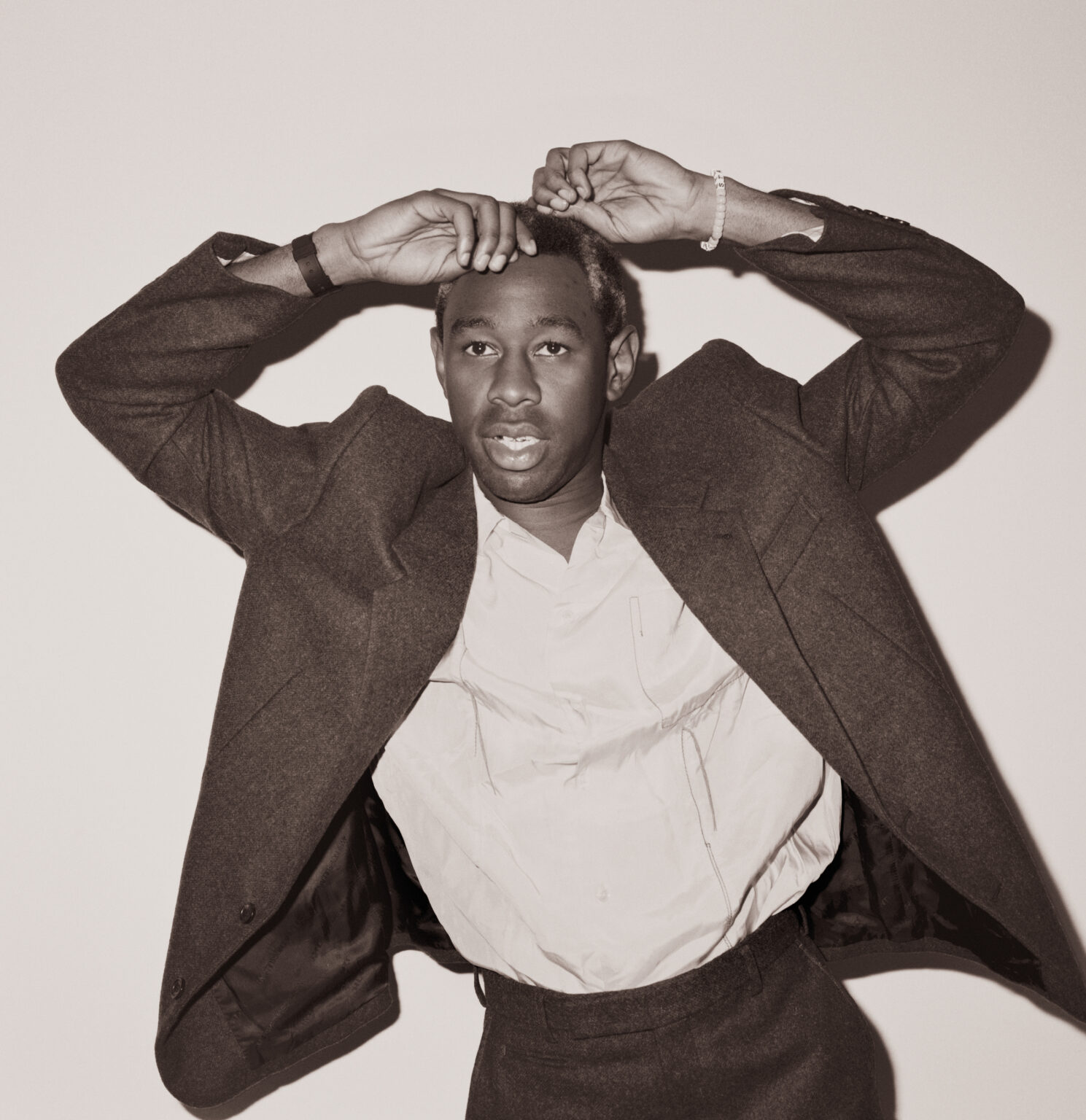

with Tyler, the Creator

Cryptic pop star Tyler, the Creator whips up his own unique universe of music, TV, fashion and whatnot. He’s a one-man creative corporation determined to do it exactly his way, as he shows in this interview experience like no other. Tyler lives and works in Los Angeles, goes shopping in Paris and can’t go to the UK because he’s banned.

From Fantastic Man n° 28 — 2018

Text by Paul PAUL FLYNN

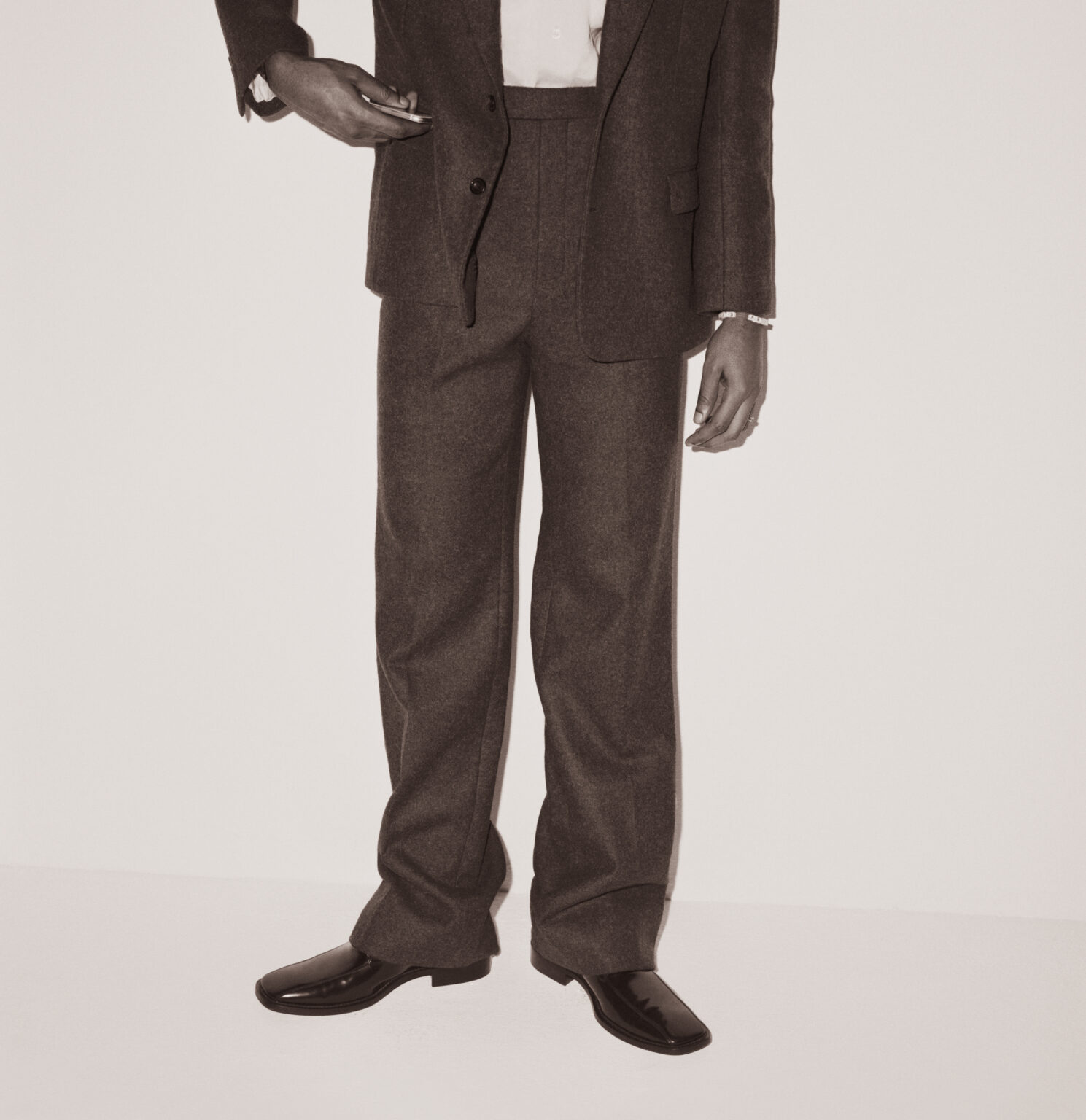

Photography by MARK PECKMEZIAN

Styling by CARLOS NAZARIO

Towards the end of a fruitful afternoon shopping in Paris with Tyler, the Creator, the hip-hop polymath reaches for his phone and reads aloud from the dream diary he keeps occasionally. It had emerged, over a lunch of spaghetti carbonara with an egg yolk the colour and shape of the sun sitting on top, that Tyler is a light sleeper. Just a light tickle of his toe can wake him during a flight.

Tyler is unusually sensitive to the whole leg area. He once kept a photo-file on an old computer, dedicated to pictures of knees. When we eventually part company, in the lobby of his hotel as evening turns to night, I ask if there is anything he feels readers ought to know about him that he hasn’t talked about. It’s been a riveting afternoon’s meander through the mind and the eyes of one of the world’s great modern inventors. “That I have no legs,” he replies.

Tyler was the operative head of the Los Angeles hip-hop collective Odd Future. They earned early comparisons with Wu-Tang Clan, though Odd Future was an umbrella name for a group of loosely connected solo artists, not a group with splinter factions. Tyler’s first release was 2009’s ‘Bastard’, a bold opening gambit that ran the timeless values of hardcore punk through the machinery of hip hop and skronk jazz, filtered by the sensibilities of an ambitious 18-year-old with nothing but self-belief on his side. Tyler had engineered for himself a camera-ready persona, inspired in part by watching Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis dancing on YouTube.

He has since fashioned four albums of his own and guested on most other Odd Future affiliates. He owns two houses in his home city, one of which he recently acquired, mostly because of a backyard which looks out over the Pacific Ocean. Seeds from the garden’s flora danced in the wind when he first viewed it. “I knew it was for me,” he says. “It looked like a fairy tale.”

Last October he opened a store for his clothing line, Golf Wang, near the corner of North Fairfax and Oakwood Avenue in Los Angeles. He’s never drunk, smoked or done drugs. Life is his elixir, music its pulse. The rest is window dressing.

I wrongly assume his dream diary is updated on the instructions of a therapist. Tyler is quick to answer. He has never seen an analyst. “No. Not at all.” He is 27 years old. At occasional moments in his life he has been instructed to. “I’m fine, though. I’m good. I have songs for that.”

He reads aloud: “I was getting a massage in another country, in Korea, and a hitman was sent out on another rapper that happened to be in the city. I’m friends with the person. That same dude tried to kill me and Vil.” Vil has been Tyler’s security man since 2011. He is sitting in the front seat of the blacked-out Mercedes in which we’ve travelled the streets of Paris for the last five hours.

“Me and my friends ended up in Gardena,” he continues. “That’s a city next to Hawthorne.” Hawthorne is the neglected Los Angeles suburb where Tyler grew up. “We went to Raleigh’s – it’s a restaurant we like – and I saw two fights. My mom crashed into a pole, because she was driving us. I hit my head in the car. The people that were fighting were people that I used to go to school with, and they said, ‘Wassup?’ and we start talking. I was in some old slave house and looking at the interior of it, for some reason.” He looks up. “There was a lot of pink,” he adds. “It was weird. This was a week ago. I have a very active dream life.” He has three or four a night. “I just happened to write that one down when I woke up.”

Tyler places the phone back into the pocket of his trousers and smiles. His grills glisten. “All of these are dreams,” he says. He could be talking to the air, the car, Paris, Vil, his career, me.

MOISTURISER

Tyler, the Creator lifts up his flat-cap and scratches his head, revealing the fabulous cheetah-print hair he dyed for this year’s Grammys. “I always told people that if I was white I would definitely have a mullet and it would be royal blue. But I never did it. Then one day I was just, like, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to dye my hair cheetah-print.’” It is easy to maintain, he says, with just a touch of moisturiser after showering. His tells me his hair never grows.

His last record, ‘Scum Fuck Flower Boy’, was a nominee for a Grammy, marrying his former irascible musical petulance, the abrasive irresponsibility of his youth, to fresh, clean, strangely commercial, even adult angles. ‘See You Again’ sounds like it could have been written for the soundtrack of ‘La La Land’, had the film been scored by someone with balls. ‘November’ is like a chilling novel sprung to life. It is rich, rewarding listening.

From the outset, Tyler rejected authority. He rapped the un-rappable, the obscene. His imagination spewed into his music like controlled rage. Nothing was beyond humour. There were no red lines. On the opening song from ‘Goblin’, the record which first brought him to a wider audience, he asserts “I’m not homophobic,” before holding a beat to deliver his double-bluff punchline: “Faggot!” It frightened the establishment in the exact way that unfiltered teenage imaginations will for eternity.

DUMBASS

In August 2015, Tyler was turned away at the border from entering the UK for various festival dates by the then home secretary, later prime minister, Theresa May, for “posing a threat to public order.” On his Tumblr account, Tyler’s manager Christian Clancy wrote that they’d received a letter from the Home Office, citing lyrics he’d written for ‘Bastard’ and ‘Goblin’ five years previously.

“I’m dark-skinned, man,” sighs Tyler. “I get it.” He is still unsure when he can return. “Because I’m the first person that this happened to. So there’s nothing to look at and gauge. It sucked. It is what it is. But hopefully it will get figured out. It happened. Now we’re figuring out how to un-happen it. When it does un-happen, we need to make people aware to make sure that it doesn’t happen again, if people give a fuck enough.” The irony of Tyler becoming a news item is that he never watches the news. “I don’t want to watch it. The news used to scare me as a child. I didn’t like to watch it.”

He thinks ‘Scum Fuck Flower Boy’ is his best album. “It’s more accessible, easier listening. I got great hooks, the beats are great, shit doesn’t need taking out. It’s cohesive. The album art is fucking flawless. I get all my points across. The features are done well. I found my version of writing a pop song but still a rap song. I still get weird musically, but it’s not too gross.”

Just because it’s his best doesn’t mean it’s his favourite. “‘Cherry Bomb’ is my favourite,” he says, of the immediate predecessor of ‘Flower Boy’. ‘Cherry Bomb’ is an excursion into hardcore abstraction that tanked commercially, threatening to derail his career as well. The Grammy nomination for ‘Flower Boy’ was an establishment nod to it being firmly back on track. “That validation is not a make or break. I know I’m good at whatever I do, but that’s a little cool extra thing to have.”

Tyler’s speaking voice is the exact same gleeful baritone, punctuated with the booming bass notes of an old movie trailer announcer, as his rap delivery. Sometimes on record it can deliver genuine malevolence and menace. In person, it is soothingly butch, like talking to a young Barry White after a spoonful of Ritalin, punctuated by the occasional dot of carefully planted hysterics. He is a reactively witty man, like a blue-chip stand-up comedian; he notices the texture, shape and colour of everything, like a poet. At certain points throughout the day, Tyler’s conversational metre slips into the rhythm of the music playing on the radio in the car, one of the bonuses of spending time in the company of a disciplined professional orator whose life is spent thinking about the way words and beats best coalesce.

I wonder aloud why Tyler likes to document his dreams.

“I don’t know,” he says, shrugging.

It is his favourite response.

“I’m a dumbass,” he says. “I’m a stupid bitch.” He taps the shoulder of his security guard in the passenger seat. “Right, Vil?”

“I can’t agree with you on that,” says Vil.

“Why not?” says Tyler.

“I’m entitled to my own opinion,” says Vil.

“You are entitled to your own opinion,” affirms Tyler.

“I don’t think you’re dumb,” says Vil.

“Whatever,” says Tyler.

“I think you’re a crazy tiger,” says Vil.

“That’s weird,” says Tyler. “Don’t say that to me.”

We have arrived at a new destination, a vintage shop in which Tyler will briefly consider the sartorial value of a pair of overalls. “I don’t like fashion,” he says. “But I like clothes.” He doesn’t buy anything.

LIBRARY

Let’s flip back five hours.

The purpose of the shopping trip is for Tyler to buy a book of the Comme des Garçons archive he hasn’t been able to locate in America or online. It is a precious commodity he intends to give pride of place in the library of his new house. We’re first introduced in the courtyard that splits the two separate wings of the Comme store on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Tyler has a friend, Travis, in tow and Vil at his side. The three are talking about the strange nature of “indigenous” cuisine. It’s 2.30pm.

“French toast is weird in France,” says Travis.

“Belgian waffles are weird in Belgium,” says Vil.

“America takes everything,” says Tyler, “and makes it dumbass weird.”

Tyler notices a strikingly handsome assistant in the store as we leave. “He was gorgeous,” he says, to no one in particular. “Did you see his beautiful eyes?”

Like Tyler’s records, the day takes pleasingly impulsive twists in unexpected directions. I began the day’s shopping expedition from the hotel to the Comme store in a Renault Espace people-carrier, alone, trailing the Mercedes he’s hired for his time in Paris. From Comme to the next destination, 0FR. bookshop and gallery, Travis travels in the Espace and I sit next to Tyler in the Merc. That arrangement continues for the rest of the day. A recorder is switched on for the six consecutive journeys that take place in between. While he’s shopping, I watch him, quietly mesmerised by his funny, dutiful, inquisitive manner. Due to the sluggish nature of Parisian traffic and Tyler’s cordiality in offering an undiluted, bird’s-eye of his world, a lot of talking gets done in these car journeys.

During the trip to 0FR., he winds down the window, noticing another model-esque, slim blond man walking aimlessly, artfully across the street.

“This is fucking crazy,” he says, wowed by the vision before him. “Look at what the fuck is going on. This is insane. This is fucking insane. Why didn’t we…? What the fuck…? Where were they yesterday? Oh, shit, this is fucking crazy. What is going on?” He asks if it’s fashion week. That’s next week. “Oh, they’re here for castings?”

I ask him to explain for the tape what he’s just seen.

“Nah, it’s just beautiful people. He was gorgeous, dude. Jesus Christ.”

At 0FR., Tyler spends a clean $700-plus on art books, including ‘Homo Americanus’, a compendium of the work of the brilliant graphic artist Raymond Pettibon. Watching Tyler stand upright in a chic bookstore, with his animal print hair, Aertex golfing polo shirt, beige slacks, cap, white socks and sandals carrying the book’s title under his arm makes a fleetingly potent image. He talks to another tall blond man at the magazine stand. “Did you see that?” he says as he leaves. “Gorgeous.”

The hunt for the Comme des Garçons book ends later, downstairs at the clothing shop The Broken Arm, where an assistant tells him it is all but impossible to buy any more. Tyler consoles himself by rapping slowly, quietly about the US government with contrapuntal emphasis on long, heavy syllables to the bracing techno playing on the shop’s stereo.

He looks at a rail of Céline womenswear. He gives Phoebe Philo a special place among the upper echelons of the contemporary fashion canon. He is actively worried about what will happen now that Hedi Slimane has taken over his favourite brand. “I wonder what he’s going to bring,” he says. “It’s been nine, ten years and I guess she wants to leave, but I just don’t want the beautiful marble and the plants and the colour palettes to turn into all black, skinny, heroin-looking white boys. Ah, man, I just don’t want it to lose that.” We walk the streets for a while. He buys a cookie, then enquires about a €260 pastoral tapestry in a shop of curios, mostly selling old wartime paraphernalia.

OKRA

Tyler is not so much a consumer as he is one of mankind’s great beauty scavengers. His eyes are hungry. Sometimes that translates into a vernacular halfway between frat-boy humour and gay porn (“I am pregnant!”), but often it is a thing of tranquil reflection. There is something uniquely transparent and simultaneously unknowable about him.

“I work off how shit looks for the most part,” he says, before choosing an unlikely example. “Like okra. I don’t like okra. The food is gross. But I love so much how that word looks. I can’t explain it. It’s all face value to me. If it looks good, then it’s the most beautiful thing in the world and I don’t care what it is. I’ve seen pastries that look so beautiful I didn’t want to touch them. Buildings. Tyres. Bags. People. Oh my God, there is something really pretty about your ear. Can I take a photo?” He’s as flippantly sensual in talking about bees as he is about beautiful boys. “I just think bees are really beautiful. They’re really cool. And I love flowers. Flowers are cool.”

Having been one of the most usefully prescient soothsayers of where culture heads next for the past nine years, Tyler has arrived at an interesting point. Though 2017’s ‘Flower Boy’ was clearly his most pop album yet, it arrived on a contentious note, as speculation swirled around the directness of some of its lyrics. On the fizzing pop cut ‘I Ain’t Got Time’, which loops the familiar jangling sample from Bel-Sha-Zaar’s ‘Introduction’ that Deee-Lite also deployed to open the inimitable ‘Groove Is in the Heart’, Tyler includes the line, “I’ve been kissing white boys since 2004.” There is a warm reflection on his sexuality in the song ‘Garden Shed’, a subdued configuration of nature and nurture.

He knew these casual revelations would generate gossip. He didn’t care. “It’s still such a grey area with people, which is cool with me. Even though I’m considered loud and out there, I’m private, which is a weird dichotomy. The juxtaposition of loud and quiet is weird.”

It’s not precisely clear whether the men he admires vocally and openly are magnetic objects to look at or engage with. He comments on beautiful women, too, in company and in song. “Such pretty eyes,” he says about one. He smiles his dazzling beam from the car at an old lady sitting on a passing bus who catches his eye. He likes the look of a street cleaner in his matching green-and-yellow hi-vis work-suit. His scavenging for beauty doesn’t end with humans. He shows me a picture on his phone of a peach covered in mint-green mould. “Nature has the most beautiful palettes.”

The book hunt abandoned, we have lunch and then visit a skate store and a thrift shop recommended by his chum A$AP Rocky, with whom he’s been DMing intermittently all day. At another point he takes a call from Jaden Smith. He signs off both with his fantastic adieu: “Send dick-pics.” “I always tell people to send dick-pics when I hang up, because it’s so awkward. Like, what the fuck did you say?”

Jaden had teased him that he’s hired a whole cinema for them to watch the recent Spielberg film ‘Ready Player One’ tonight. When he signs off the call I ask if he really wants to see the film again? “Yeah, no. I didn’t like that movie. Because I’m not 11 years old.”

DISTRACTION

Tyler and Rocky have been in the studio together in Paris, working on a song, ‘Potato Salad’, set against a loop from an old track Missy Elliot produced for Monica. Last night, midsession, weed appeared. “I went in the room and took the blunt out of somebody’s hand, threw it on the ground and stepped on it and said, ‘This is a distraction. This needs to stop. We are here to fucking work. Not to hang out.’”

If the magic isn’t happening in the studio, Tyler has learned to content himself. “You just sit there and look at Gary Numan videos for five hours.” In the absence of stimulants, maybe work is his drug? “Fuck that. Clear mind. At least once, goddamn. We’re drug-free at night.”

Tyler says he doesn’t know why he’s never been inebriated. “Why haven’t you wrestled a tiger? I don’t know. I just don’t want to drink.” He returns to the idea of taking everything at face value, making life decisions reactively, from the gut. “I know that I don’t want to be that drunk guy,” he says. “But I do know I want to hit a jump on a dirt-bike. I can look at that and say: ‘I want to do that.’ I’ve never seen anyone drunk, like, ‘Damn, I want to be that.’ So, I guess I just naturally got it pushed into my head that I have no reason to go over there and get fucking drunk.”

Unlike his buddy A$AP Rocky, he sees no attraction to the party, the mythic epicentre of hip hop, from kids learning to scratch to crowds in basketball courts in the Bronx at the end of the ’70s to Kanye West and Kim Kardashian’s luxe Calabasas kitchen in the 2010s. “I love sunlight,” he says. “I hate night-time. It’s ugly. It’s just dark and you can’t see. Everything is fucking closed. What do you do at night?” Going to a nightclub holds no allure. “It’s not music there that I like. I’m not trying to talk to the girls. It’s sweaty. I don’t drink and smoke. You can’t see because they don’t keep the lights on. I can just not go. And if you’re into that shit, I get it. It’s great. Just not for me. I never did.”

He knows the mythic rock significance of the age of 27. “Yeah, but a lot of those people were fucking shooting heroin in their ass. So I kind of think I’ll be OK. A lot of them died from actual heroin being shot in their assholes.” He pauses, for fear of sounding unsympathetic. “That’s exaggerating, but you get what I’m saying. I don’t know man. I’ve never had the desire to shoot heroin either. But hey man, if that’s your thing, man, do your thing.”

When he was at elementary school, Tyler had a new favourite record. “I remember being nine and buying Jamiroquai’s ‘A Funk Odyssey’ album,” he says. “And not being able to play it for the other kids because they were, like, ‘Yo, this shit is fucking gay.’” Hip hop’s party-time club bangers were all over the playgrounds of Hawthorne. It was the years of Ja Rule and Nelly, good time guys, muscles, Courvoisier, pool parties, women in lingerie, an aesthetic directly antithetical to that forming in young Tyler’s mind. He says the name-calling didn’t bother him. “Er, I mean not really. Call me whatever. It alienates you as a child. But I was tight. I’ve got my music back home and my books and videos. I wasn’t triggered.”

ANDRÉ

Tyler changed school most years, a fact to which he attributes his gregarious nature and his instantly amenable agility at connecting with strangers. At kindergarten, he presided over his class graduation ceremony, aged four. He got used to being looked at early. “I’ve always been a character. I have the energy where you look at me. I can’t walk in a room and not have people look at me. I don’t know whether it’s my ears or my smile or what, but you just know.”

When he was twelve, his mum bought him a copy of OutKast’s ‘Speakerboxxx/The Love Below’ double epic. He opened it three days before Christmas and played it on repeat. Hearing ‘The Love Below’ turned his life around. A bridge was built by OutKast frontman André 3000 between the world he came from and the wild fantasia his active little imagination dreamt of, a universe of Technicolor wonder, connected to nature and humanity, funny and regal, attached to beats in a sumptuous new way. “He only raps on what, three songs?” Tyler says. ‘The Love Below’ was a record filled with the limitless possibilities of life and taste. A suite unafraid of its strangeness, celebrating its theatre, exploding like a timebomb, upsetting the conservative, stagnant world of early ’00s commercial hip hop. It was 2003. “It’s in my top 10, ever.” It sounds like his ground-zero record. “I love André so much.”

I ask a question over lunch, perhaps connected to all this, perhaps not: Why did you start talking about your sexuality on ‘Flower Boy’, Tyler?

“I don’t know,” he says. This time, he elaborates on his favourite response. “It’s a literal question and the thing about humans is we hate not having an answer. We hate not being in the know. So people will bullshit answers, make shit up, instead of being just, like,” he shrugs his shoulders, “I don’t know. There are some things that are just unexplainable.”

WOLF GANG

When he first appeared as an erratic teenager, Tyler, the Creator looked like a new accent for hip hop. He was both cute and terrifying. He was half cartoon, half slasher movie; half fairy-tale, half nightmare. “Exactly,” he nods, “100 per cent.”

Odd Future was the name he’d thought up for a magazine in his teenage bedroom. “Because I liked books,” he says. “I was going to make a magazine that kind of was a hub for all the different things I liked. All the photographers that I fucked with who were coming up, all the artists, all the musicians, all the rappers. Then it kind of just formed into this rap artists’ music thing.”

He shows me another screengrab, the background wallpaper of his phone. “I look at this because of the music I’m making,” he says. It’s a shot of children by the sea. “I want to be the third person in here. It’s an attitude. What the fuck you looking at? It’s summer vacation. They’re eating ice cream on this dock. But they look like they might’ve killed their parents.”

The music, visual identity and untutored energy of Odd Future cut through to the wider culture. It hadn’t been brokered around a Perspex record label boardroom table with an eye on profit margins. It came straight from disenfranchised teenagers’ imaginations. The “O” of Odd Future was a cartoon donut. Sinister cats were a repeated visual trick. Children had their faces scribbled over and eyes poked out. Of the images he created for the early years of Odd Future, his favourite was the jacket of the first Mellowhype album. “All of that was so important to me. Like, that shit’s important.” It all represented another new pathway for hip hop. “I don’t really like the way the city looks. I like flowers. I didn’t like weapons. I didn’t like a bunch of girls dancing in the video, I liked…”

You liked cats?

“I liked the colour pink and skate-boarding.”

As each member of Odd Future appeared – there were a lot of them: Hodgy Beats, Domo Genesis, Syd tha Kyd, Mike G, Taco Bennet, Left Brain, Jasper Dolphin, Earl Sweatshirt, Lucas Vercetti, Matt Martians, Casey Veggies, Frank Ocean, L-Boy, Pyramid Vitra, Sagan Lockhart – with a new record, a YouTube clip, a funny aside, a horror story of their times set to song, a live show bottled full of raw teenage wit and vitriol, it felt like watching the opening credits of a scintillating new film unfold, as captivating on the energy and purpose of wasted youth as anything by Larry Clark.

“I just knew that we were the outcasts,” he says. “Now that sucks. ‘We’re weird, we’re outcasts, we’re the millennials.’ But the shit those niggas were into and doing in 2007 and ’08 was real life, not dumbed up. It was our lives.”

Odd Future elongated to become the more esoteric initialism OFWGKTA (Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All). “The shaping of OFWGKTA looked so foreign. But I was aware that when you see that, there is only one thing that could be.” The cats had reason. “I’m allergic to dogs so I could never play with them or be around them, which made me grow a weird disdain for dogs. So I naturally was attracted to cats. The fact that it was Wolf Gang with cats I just thought was funny. So I started putting cats on shirts.”

From the start it was clear that Tyler was the ringmaster of Odd Future’s early destiny. “I was always the one that would jump in front of the bus and get hit to make sure everyone can cross. I was always: no man will be left out, everyone comes. That was always me. I spoke up for everyone. If there was a problem, I always knew what was going on. They trusted me. It worked out.” How did he know it would? “I kind of didn’t. But I had nothing to lose. So the best we could do was try.”

When his great friend Frank Ocean started to fashion his crossover 2012 masterpiece ‘Channel Orange’, the creative reach of Odd Future started to reflect its early brattish ambition. “Being around him when he was making it was just fun,” says Tyler. “It was, like, he would rent houses and stuff to record in. I mean, I didn’t know you could do that.” He loved watching the record become what it became. “That’s a big homie. His shit is tight.”

Tyler started the clothing line Golf Wang in 2011 for the same reason he started making records. “I make music I want to buy and clothes I want to wear.” His only concession with Golf Wang is coloured socks, which he would never wear. He only wears white. With the label, he has found a way of not just being listened to and looked at, but worn, too. The clothes are nominally what you might call skatewear. They are instantly recognisable and fit part of Tyler’s central maxim for wearing clothes. “I like dressing like an old man.”

Golf Wang is a continuum of his world, the way he sees things. He is one of a number of menswear-design entrepreneurs who have reshaped the way young men engage with clothes, offering an entry point and affordable price tag to counter the houses of Milan, Paris, London and New York. His personal aesthetic and cultural touchstones are as important to Golf Wang as James Jebbia’s is to Supreme, Lev Tanju’s to Palace, Virgil Abloh’s to Off-White and Kanye West’s to Yeezy. Jebbia offered him an early ear for advice. “James was supportive since day one. James was always really nice and would give me some gems that he didn’t need to, regarding my clothes and what I was doing. He’s really nice. Cool kid, I love that dude.”

YONKERS

The world of Odd Future and Tyler, the Creator quickly attracted admirers. His heroes began circling. Kanye West tweeted about his song ‘Yonkers’ from the early album ‘Goblin’, then Pharrell Williams asked him to remix the N*E*R*D song ‘Inside of Clouds’. They became friends. He finally met André 3000 backstage at Coachella, for the OutKast reformation show. “Man, that was crazy just seeing him in person.” He met another great hero, the comedian Dave Chappelle, at one of Kanye’s shows. “I saw him, he saw me, my heart dropped. Dave Chappelle was how I learned how to move my arms. I love him so much.” The train continued. Chappelle introduced him to Stevie Wonder. “That shit was mind-blowing to me.”

From an artistic perspective, these moments made sense. As a schoolkid, he’d looked at Pharrell and Kanye and seen something of himself reflected back at him. “I always go back to Pharrell winning those Grammys or Kanye winning those Grammys. Making what they make opened the door for me to do this. Just being a black kid who wasn’t painted as a stereotypical black kid in the city, with them up there making great music and being influenced by different things? Oh, for sure. I could definitely do that.”

MOUTH

It is his job now to pass down his success to kids just like him. “Seeing people that look like me,” he says. “It’s even in our heads. I told someone I wasn’t supposed to make it out of Hawthorne. He was, like, ‘Yes you were.’ You know, it’s planted in my head at a young age that I’m not supposed to have the things that I have. It’s sometimes a good reminder to see guys who look like me doing really cool shit. And they’re doing it from making really cool shit, that’s not them sticking to a stereotype or behaving in a certain way because they have pigment in their skin colour. That makes me so happy.”

Paris is floating by the window as he speaks. “Sometimes I even trick myself. Wow, I’m not supposed to have this.” He shakes his head. “Yes, I am. We’re all supposed to have it. I don’t come from a rich background. So I work. And I am never, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever going back to that, dude. I will never be not comfortable. Or I will kill myself.”

Back at the hotel, Tyler settles into a comfy chair, surrounded by his new books and magazines. One is a pop-out that opens into a poster. Maybe he’ll put it on his wall back home in his new house with its lovely garden, in the library, not smoking or drinking, just imbibing all that is around him, all that Tyler has created.

“You could get it framed,” suggests Vil.

“The only thing I’m going to get framed,” says Tyler to his bodyguard, “is my dick, with your mouth.”

“How could I frame that masterpiece,” says Vil.

They both laugh.

Tyler takes a moment to reflect on the difference between beautiful and ugly. “Um, they could be the same thing on different spectrums,” he ponders. “Everyone has seen something that is ugly… but you’re so intrigued by it that it is the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen. It’s the same thing. There’s songs like that. I love rough drafts that aren’t finished and fleshed out and mixed horribly. That’s fucking fire. No, don’t change it. Don’t perfect it. Don’t plastic surgery it. Leave that shit wrong and gross. I love that.”

During the day, there has only been one conversation that Tyler shuts down. Over lunch I asked if he has ever been in love. “I don’t want to talk about that,” he says politely. It turns out he just doesn’t want to give too much away right now. “Um, that’s the next record.” Tyler is his own boss. He doesn’t know when the record will be finished or released. He will make that decision when he’s happy with it. He intimates that it may be his most radical artistic about-turn yet.

I ask him one last question.

Do you feel like a beautiful man?

“I’m beautiful,” he says. “I’m gorgeous. My mind is beautiful. I’m beautiful. That’s a fact. And I’m ugly at the same time. That’s crazy, right?”

Photographic assistance by Brian Bee and Fred Mitchell. Styling assistance by Anna Devereux, Margrit Jacobsen and Mackenzie Grandquist. Hair by Ronald McCoy III. Make-up by Sarah Ulsan at The Visionaries using Malin + Goetz. Tailoring by Suzy Yun. Production by Rosco Production. Retouching by IMGN Studio.