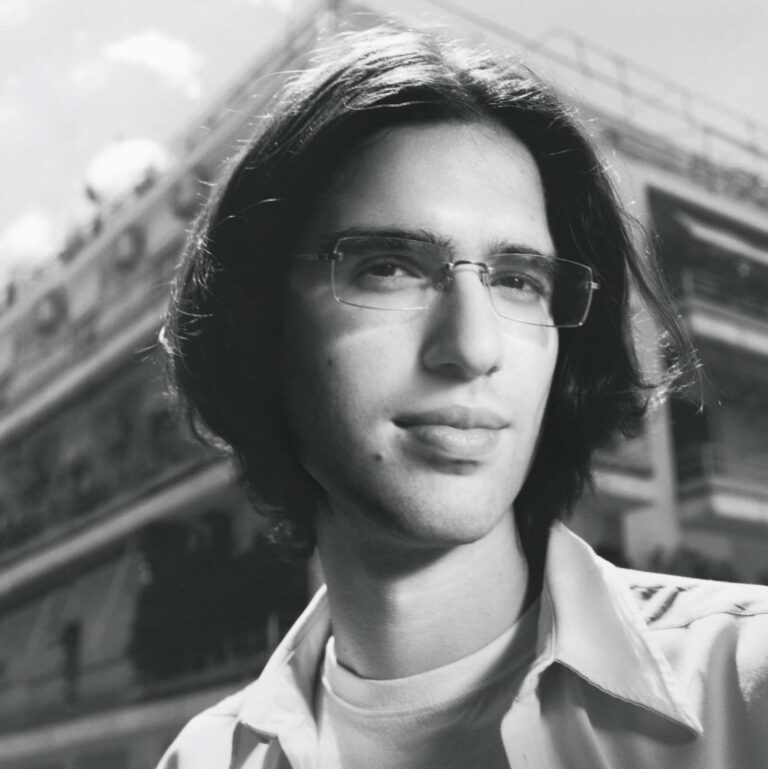

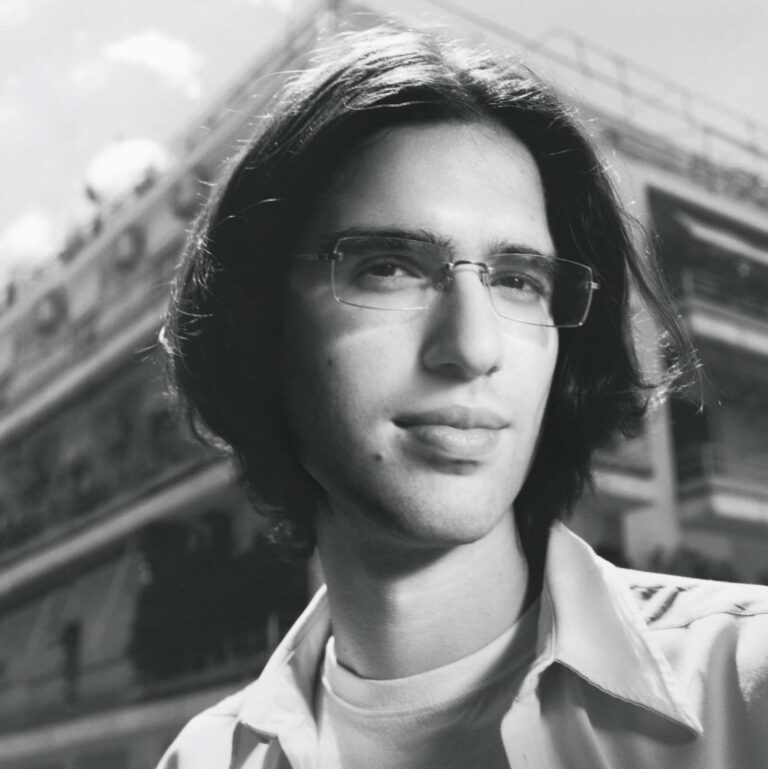

Michael Kardamakis

No. 1 collector and archivist of Helmut Lang

It has taken a young Athenian three years and no money to build the world’s biggest archive of vintage Helmut Lang fashion. Parts of it are for sale, but they’re not cheap and he’s keeping the best finds for himself – though those are not necessarily the rarest items. Michael Kardamakis loves the normality, the mundanity and the consistency of the Austrian designer. Previously, he collected coins, stamps, phone cards, Pokémon and hardcore punk vinyl. Now his archive attracts fancy clientele from across the globe. It’s called ENDYMA, which is Greek for garment.

From Fantastic Man n° 30 — 2019

Story by GERT JONKERS

Portrait by MARK PECKMEZIAN

Selfies by MICHAEL KARDAMAKIS

“Basically, it goes like this,” says Michael Kardamakis, who was born and raised in Athens and has an elaborate way of expressing himself via the most peculiar wording from the world of academia (“empirical,” “sclerotic”), technical terminology (i.e. the difference between “sateen” and “satin”) and a lot of “fucks.” “I come from a family of book publishers and priests. The Orthodox community. There was a lot of culture around when I was young, but nothing in terms of fashion. As a teenager I’d go to the high street, trying to find stuff to wear, and I was browsing ASOS endlessly, but I couldn’t find anything. And then one day I realised, ‘Oh wow, eBay, that’s where you find the good stuff.’”

Michael studied art history in Norwich, a handsome medieval city 190km north-east of London, which is where his shopping hobby got really serious. “The research for my degree was all about contemporary fashion. I was reading and writing about clothes, and I was buying clothes just to see them. In Norwich or in Athens I was never near enough to Selfridges or Browns to go see these clothes and try them on, so that’s what I’d use the internet for. If I saw some Tom Ford or Rick Owens or Ann Demeulemeester and it was cheap, I’d buy it. I bought all these random Belgians that nobody knows about. And what I couldn’t wear myself I would then flip again: I would just take better pictures and write slightly better texts, write a bit about the history and the fabric of the garment, and I’d sell it for a bit more than I’d bought it for.”

His dissertation was on Ann Demeulemeester’s shapes. “Like, her sleeves, and how they fall on the elbow and reach past the wrist, and how they integrate motion and texture. I was analysing fashion from a material and sensory point of view, and not in terms of semantics.”

His three years of studies left Michael with a funny feeling. “Oh wow, I can’t do anything. All I know is how to flip clothes.” Also, he was called up for his military service in Greece. “Fair enough. I was done in Norwich, I hated London, and Greece had fallen into a deep recession. Athens had zero work, but the rents were crazy cheap.” And so, military service over, Michael moved back to Athens and rented the spacious eight-room flat in which we are now talking. It’s located in Exarchia, an area that was not so long ago the city’s fanciest address (Maria Callas lived around the corner), but is now somewhat downtrodden with rents to match. “It wasn’t a conscious choice. I’m usually very methodical, but in this case, I was just lucky,” says Michael of the idea to stay in Greece and of finding his life’s vocation as a fervent collector and reseller of ’90s fashion. “Athens is great, if you live like a monk. Which I am. I have no distraction here. If I’d lived in London, I would spend too much time talking about the latest sneaker or the latest bollocks, which isn’t constructive in any way. I’m blissfully ignorant.”

VELCRO

While living in Norwich, in one of his online shopping frenzies, Michael bought a Helmut Lang biker jacket in pale moleskin with a detachable sheep-fur collar (see fig. 2). “It looked cool. I liked that it had these belts on the inside so you could also wear it like a backpack. But it was a size 50 and I was a skinny Burberry boy. I wanted everything to fit me like it was shrink-wrapped, with no breathing room. So this jacket was huge on me. I wore it for a week, then put it back on the market again.” Michael had bought the jacket for about €100 and sold it for €400. “That’s interesting,” he thought. He looked again at the address of the buyer:

3 avenue George V

75008 Paris

Wasn’t that Givenchy’s headquarters? Michael jumps up from a baroque pink fauteuil to fetch the biker jacket he’s talking about. “Well, not the actual same one I sold to Givenchy, of course, but similar. Fur collar attached with Velcro. Look at these Velcro details on the side. And the zippers. I’ve had about 20 of these in the meantime. They sell well. They go for €1500–2000 now.”

Gradually Michael’s thriving flipping business became many other things. It’s an apartment full of amazing clothes. It’s a shop, by appointment only. It’s the biggest vintage Helmut Lang archive in the world. It’s a space where design teams – from Tom Ford to Off-White and all that’s in between – come to look for inspiration, research and reference. “Kind of amazing that people fly all the way to Athens to look at a bunch of ’90s fashion, don’t you think?” he says. But it suits him just fine, especially the rental part. “It’s a win-win situation. Big brands rent clothes because they can’t be bothered to actually own them, and I make money and get to keep them.”

At some point the space got so full that Michael moved into an apartment nearby with his girlfriend, Joanna, to better separate his life from his work.

And so today, ENDYMA, which means “garment” in Greek and is the name of his business, looks like the stockroom of a fancy shop. Pairs of, say, Helmut Lang’s covetable, horizontally striped jeans hang in their dozens, in all sorts of colour combinations and in a full range of sizes. The timeline from flipper to Helmut Lang specialist is a bit blurry even for Michael himself, but he thinks he started taking the archive seriously three years ago. Three years? For an archive that holds 1500 Helmut Lang items? That means he must have purchased ten pieces per week! “That’s fucked up,” says Michael, surprised. “Well, I guess, yes. Even more, maybe. Since ENDYMA started, I’ve also had hundreds of orders. A lot of stuff has left.”

When Michael started buying Helmut, it was still findable and affordable, which surprises me, but Michael claims people were “just looking for Rick Owens drop-crotch ninja trousers” five years ago. So apart from Michael’s obsession with Helmut’s aesthetic, it helped that he could actually afford it. I ask him why he doesn’t collect any Margiela, another ’90s legend, for instance?

“Because there’s a Margiela auction happening at Sotheby’s next month,” he says. “That’s why. It’s too late.”

THE ORDER OF THINGS

Michael Kardamakis is 26 years old.

Over the course of two months, I visit ENDYMA twice. On my second visit I am introduced to Leo Mehles (see fig. 4 and fig. 6). “Leo is ENDYMA’s first-ever intern,” says Michael.

Are you good at delegating?

“No. I panic. It’s so empirical. For instance, to iron this fucking shirt,” he says and shows me a perfect-looking, putty-coloured cotton shirt with a subtle italic HL logo stitched on the left chest, “it took Leo maybe 25 minutes, half an hour. Then I did it all over again. It’s not like he did it totally wrong, but there’s a system to it where, if you iron one part and you then iron the wrong part next, it’s gonna look fucking awful again.”

What’s special about this shirt?

“This is Helmut doing a Ralph Lauren or a kind of basic GANT shirt. It’s from ’98. I have a shirt similar to this on which the wrinkles just keep coming through. I don’t know why. That’s the kind of stuff that occupies us here. We iron and we tidy up. The whole day.” Michael is being a bit unfair to himself here. Yes, he irons and he tidies up, but many of the Helmut Lang garments carry elaborate paper labels with the year, origin, factory details and all other sorts of interesting facts, all in his signature flourishing diction. His father does the layout for the labels. “He’s my graphic design slave – I know so precisely what I want that I don’t think there’s anyone else who I can ask to do it,” says Michael.

We look at the order of things on the racks, for which he’s made up a system. It’s completely arbitrary, of course.

Everything is grouped on racks by colour.

Each rack starts with lighter garments and ends with heavier garments.

Within that, it’s ordered from weirder to more basic.

The first garment on the rack is very light and very weird, and likely something sleeveless.

Then short sleeved Ts.

Then longer sleeves, which means more weight.

Then polos.

Then short-sleeved shirts.

Then long sleeves.

The final item might be a very basic piece of outerwear.

There’s no division between menswear and womenswear, I notice.

“Of course not, because with Helmut it’s all men’s, basically, even if it’s women’s. It all comes from menswear. So, after shirts you have dresses, then sweaters, outerwear, and so on. Somehow this all makes sense to me, typologically. And then, once you’re at the end with one colour, the next colour starts.”

Why is the first rack in the room beige instead of white?

“I don’t know. I think beige is a colour that’s often overlooked, it’s a difficult colour to engage with, so by putting it first it gets a bit more attention.”

It’s often interesting to try and follow Michael’s taste. He shows me a printed jersey Helmut Lang dress that looks extremely complex, with a flap of fabric running down the front, knotted and twisted, and asks me what I think.

It looks intriguing, I say.

“I don’t like it,” he says. “It’s an exercise in complexity, but it’s not very good. It’s from Helmut’s final runway collection. This is not the result of confidence.”

In terms of rarity, I ask Michael if there’s one Helmut garment that he considers his holy grail, that he dreams of finding one day? Is he fanatically looking for the super-rare jacket adorned with flattened bottle caps, from one of Helmut’s last collections?

“I don’t care about the bottle caps. They were made for the runway; they were never produced. They’re not consistent for the collection. If I get it offered, I’ll take it, of course. I have a nice leather perfecto jacket that was a sample for the runway and was never produced. That jacket I do like. It has a hole in one arm.” (see fig. 3)

He jumps up to get me something he really likes. Not quite a holy grail if you already have it, but whatever. He brings back a denim jacket from a rack containing dozens of denim jackets, the most eye-catching thing about it being a shiny metal cock ring hanging from a little loop on the left shoulder. “It’s not so much the cock ring that I like, but the chest pocket shape that’s squared off, which means it’s an early specimen. Later on, Helmut changed them to a diamond shape, which is more classic. He also did some slightly weirder trucker versions with waist pockets. There’s also a sleeveless variety with a Union Jack print on the front. I really like those.” (see fig. 6)

What do you love about them?

“Some people find the print quite cringe. I don’t mind it so much, I don’t have a memory of the British flag being misused on everything. And the printing’s done well. I think it’s a great concept. My obsession is also that this jacket is part of an entire range.” Michael has four of the black Union Jack waistcoats. “Nearly a full size range, yes.”

Michael says that he has a “marketplace” mentality: whatever he can get, he’ll get. “For you or any other visitor this archive is entirely complete. You can spend two full days here and still not see everything I have. But there’s always going to be more, no questions asked. Things that I’d love to have, like, different colourways of the same garment. Like, I want to have all the Pokémon. I know that Andreas Angelidakis, who lives around the corner, has a cock ring jacket in black, and I don’t. So that’s going to be mine one day – you can put that on the record. I didn’t have Helmut’s handcuff bracelet until recently. That was a bit lame. You can’t have a Helmut Lang archive and not have the handcuffs. They’re the closest thing to an ‘it’ item that he ever made. So now I have them in silver and gold. They look like weird bottle openers. I think they retailed for €120 back then, and they go for €500 now, so times have changed. I’ll keep these ones in the permanent collection.”

Perhaps it’s a good moment for the question: Why Helmut Lang?

“What makes Helmut so good is that he successfully managed to be seen as a visionary, to be seen as avant-garde, but he also had an affinity for real clothes. Helmut’s constructions are workwear, his alphabet is workwear. In fact, the longer he worked, and the more famous he became, the more conservative some of his shapes became. The pockets on his early denim jackets were square, and then a few years later he makes them even more Levi’s-looking. I find that a very hardcore, difficult move in terms of fashion and design. He was the coolest designer around. But around 2000, when a new wave of designers came in, he stuck to what he was doing. He still wanted to be ahead of the curve but hadn’t realised that the curve itself had changed.”

What Michael means is that Hedi Slimane started Dior Homme in 2000, and revolutionised fashion with his super slim silhouettes, sparkly fabrics, rubberised zipper details and jeans with elaborate coatings. Why doesn’t Michael collect any Dior Homme? “I think it’s an extremely strong proposal for menswear, but it’s not for me. I just don’t like it so much. It’s very dandy. It has its place, but it’s not my cup of tea.”

Back to Helmut.

“For me, it’s about the typologies, the pocket shapes, the denims. I collect everything Helmut, because an archive has to have a complete overview, but I’m not so much into the perfumes or the accessories. I’m into the fucking shirt. I think I’m going to put all the shirts I have into the permanent collection. I can’t get enough of them. I love all of them.”

Once Michael’s on a roll, he picks up pieces and rattles off trivia. “I love how consistent it is. You see this reflective thing here? This is 1995. And then this reflective thing here? 2005. That’s the way Helmut designed. He’s so consistent and you see real progression from piece to piece.”

The amount of detail Michael knows about Helmut Lang is hysterical. How does he date a garment? “It’s experiential, largely. It’s in my head. Helmut used the same label for most of the ’90s and changed label colours only to match the colour of the garment. But around 1995 the synthetic label was a bit thicker, which you can’t see from a photo but you notice once you touch it.” Goodness, I say, you should write the definitive book about Helmut.

“I know a lot of specifics, a lot of technical stuff, but very little about the models he used or the campaigns he shot, all the shit that people are actually interested in. I’m interested in the objects. That’s my motivation.”

Helmut Lang as designed by Helmut Lang himself existed between 1986 and 2005. The designer was first based in Vienna and moved to New York in 1997. He sold a majority stake in his business to the Prada Group in 1999, and in 2005 the whole thing unravelled; Helmut quit fashion and focused on his work as an artist, and Prada sold the name Helmut Lang to an investor. The brand still exists, but Michael doesn’t care about anything from Helmut Lang after 2005.

Despite the huge legacy and simple wearability, Helmut Lang never really sold particularly well.

“That took me a while to realise,” says Michael. “It’s interesting. The brand closed for a reason, whether you like it or not.”

RESTORATION

At some point while we’re strolling through the ENDYMA apartment, Michael opens the back room: “The behind-the-scenes situation,” as he calls it. Here’s some stuff that’s just come in and needs processing: cleaning, ironing, repairs. “Restoration is a big part of my work. You’d be surprised. I have five different tailors who specialise in different things. One’s really good at stretchy things, one’s for leather, one for re-dying. We do pretty invasive repairs. Check out this guy,” he says of a cropped green bomber jacket hanging on the rack.”

“It’s a great jacket that once had these elastic straps, like belts that could be adjusted. Someone cut them off. I’ve been looking for three years to find the right army green elastic, and I found a roll, but it’s the wrong width; I need two different widths, which I finally found.” Then he points at the ribbed knitted waistband of the bomber jacket. There’s a little bleach stain at the back. “That kind of bothers me. I want to see if I can remove this whole part and turn it inside out.” Michael did that once with a shirt that had burn marks on a sleeve. “It was made of double-faced nylon, so we took off the sleeves, turned them inside out and put them back on the opposite arms. My tailor thought I was crazy when I asked him to do it, but it worked.”

Two giant trolley bags with clothes spilling out of them stand in the middle of the room. They were dropped off last week by a gentleman from New York who was on his way to the Peloponnese and wanted to see if Michael would be interested in trading them. “Weird shit,” says Michael. “All in a pretty disgusting condition, mould growing on them, some extra funky shit as if it’s been put in a dungeon for years.” But there’s some great finds in there too: a Helmut Lang bulletproof vest, the famous aviator chaps but in black instead of the usual army green. “A nice mix of things, some monumental acquisitions,” he says. He’ll have to figure out what he’d like to trade it for. “The guy clearly knows what’s good,” says Michael.

There’s one crammed room in the ENDYMA premises that has absolutely no Helmut Lang in it, but instead about ten racks full of “other” designers that Michael collects on the side. There’s a lot of Raf Simons and Burberry from the Christopher Bailey era, Nicolas Ghesquière for Balenciaga, Veronique Branquinho, Italo Zucchelli for Calvin Klein. “I’ve started to like Dirk Bikkembergs,” says Michael. “Ninety-five per cent is awful, but I like the shoes.” There’s a selection of leather bags by a Belgian designer who Michael begs me not to mention the name of. “It’s my other big obsession, after Helmut, and I’d hate it if the prices go up just because people know I’m interested.”

Which is an actual danger. Michael is very active on Instagram and happily posts Stories about the clothes he collects, often to the bemusement of his followers. Why is he raving about a ’90s denim label called Destroy? What’s up with that colourful sweater by James Long? Half a rack is dedicated to Dexter Wong, a British label that was only somewhat popular in the mid 1990s. “I like it,” says Michael. “It’s kind of garbage, but it has a level of confidence that could almost be Helmut. Here, a T-shirt, a matching jacket in the same shiny fabric and, what the fuck, matching jeans. I bought them separately. Yeah, this is what I do when there’s down-time on Helmut.”

Between my two visits to the ENDYMA apartment, I speak to Max Pearmain, the London-based stylist who’s a big Helmut Lang collector himself, and who trades “quite a lot” with Michael. Another fun fact: Max is from Norwich, where Michael studied. They met on eBay, though, and when Max first contacted Michael, the latter was replying from a naval ship, on military duty. “Michael’s collection is so advanced,” says Max. “He’s heads above all other Helmut collectors; it’s a joke.” Max particularly likes how Michael is there to protect the garments, restoring them, colouring them back to their original state. “He has an almost emotive connection to Helmut. He’s a lot more tangible than other collectors. He’s just better.” But Max, too, sometimes finds himself puzzled about some of the “other” designers that Michael posts about – which is indeed a fascinating thing about Michael. His obsession for Helmut is so precise, but it’s impossible to predict what else he’ll like. “He posted some jumper the other day by some really awful designer that for the sake of politeness shouldn’t be named here, but who really isn’t up my street,” says Max. “I mean, it’s not even my town!”

These other designers are highly flippable as far as Michael is concerned, but the room turns out to be popular with designers visiting ENDYMA for inspiration. “The stuff in here is sometimes more relevant in terms of research,” says Michael. “Helmut is so sclerotic. It’s one vibe. And if you can’t deal with that vibe…”

GETTING STUPID

Michael has never met or spoken to Helmut Lang. He has no desire to, either, although he’s quite thrilled that he DMs on Instagram with the stylist Melanie Ward, Helmut’s long-standing collaborator. “I owe my fucking life to Instagram,” he says. “I do business on Instagram, interviews, I make friends around the world. I’m this random Greek guy, talking to these incredible people.” Michael has a jolly persona on the social media platform, and the pictures of the clothes he receives, sells, irons, repairs never really look too slick or too polished, which seems a clever strategy. Obviously, Michael also has great marketplace skills. Athens, he’s discovered, is the perfect time zone for international communication. “It’s afternoon in Japan now, a good time to be shopping in Asia, and then I have the American market waking up the rest of the day.” He uses auction sniping software for last-minute bidding and hints at a whole portfolio of tricks to manipulate the process of buying online. “I could write the guide book for it,” he says. But he won’t, of course.

Does the archive make Michael happy?

“The process of collecting makes me happy, very happy, yes. Very fulfilling. My work is everything to me. Okay, I have a great relationship and I feel stable, emotionally, but my job gives me confidence. I always wanted to be good and be recognised for it. And the fact that it’s working out is amazing. I feel like it’s happened very organically.”

Were you always a collector?

“Ever since I was young. Coins, stamps, fucking pay-phone cards, Pokémon cards, hardcore punk on vinyl. I’m also really nostalgic.” The pink sofa and chair we’ve been sitting on are heirlooms from his great-grandma. “I’m really obsessive, everything goes into folders, nothing gets thrown away. It fits my character, this hoarding typology thing. It makes me happy, also when I see what other people who call themselves an ‘archive’ are doing. Basically, everybody and their dog has an archive these days and they’re selling shit. It makes me feel good about what I do.”

But if, God forbid, the archive burned down tomorrow, he insists he could start all over again doing something completely different. “Maybe I’d go back to school? I’ve been to university for three years and it feels like I haven’t learned enough. I’d really like to study something else. I now have this old person’s routine where I have a nice home, I walk to work, I’m in Athens where nothing ever happens, I’m not reading anything and I feel like I’m getting stupid. I’m just pressing shirts.” Then he gestures with his left arm, flaunting a tattoo on his wrist that says, in bold capitals, “NO REGERTS.” Isn’t it brilliant?