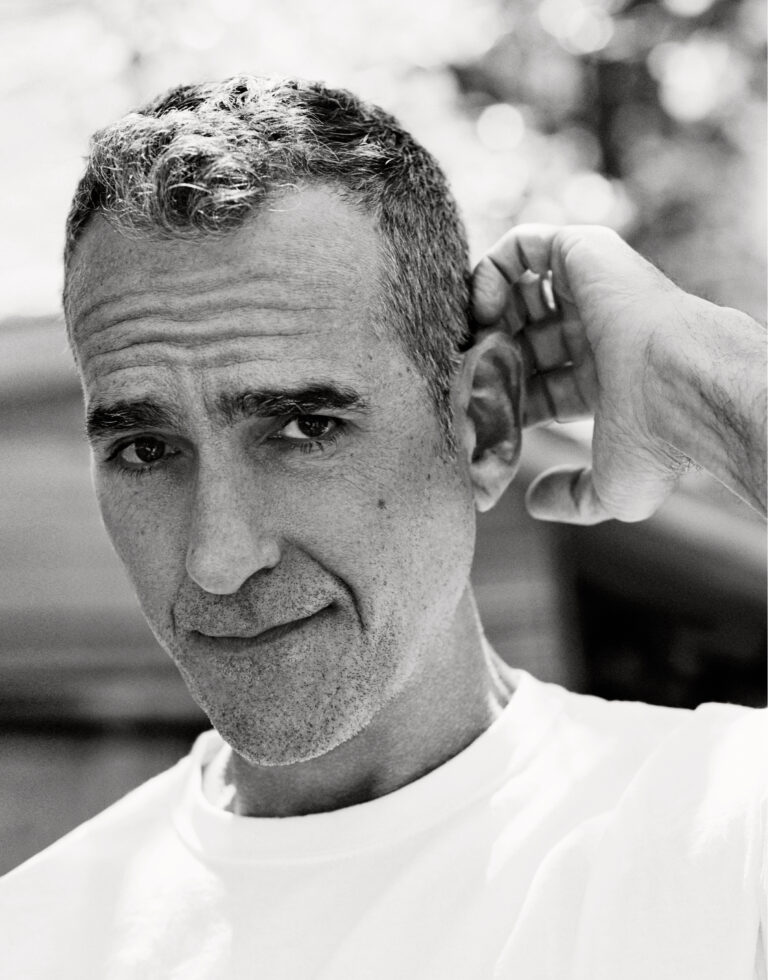

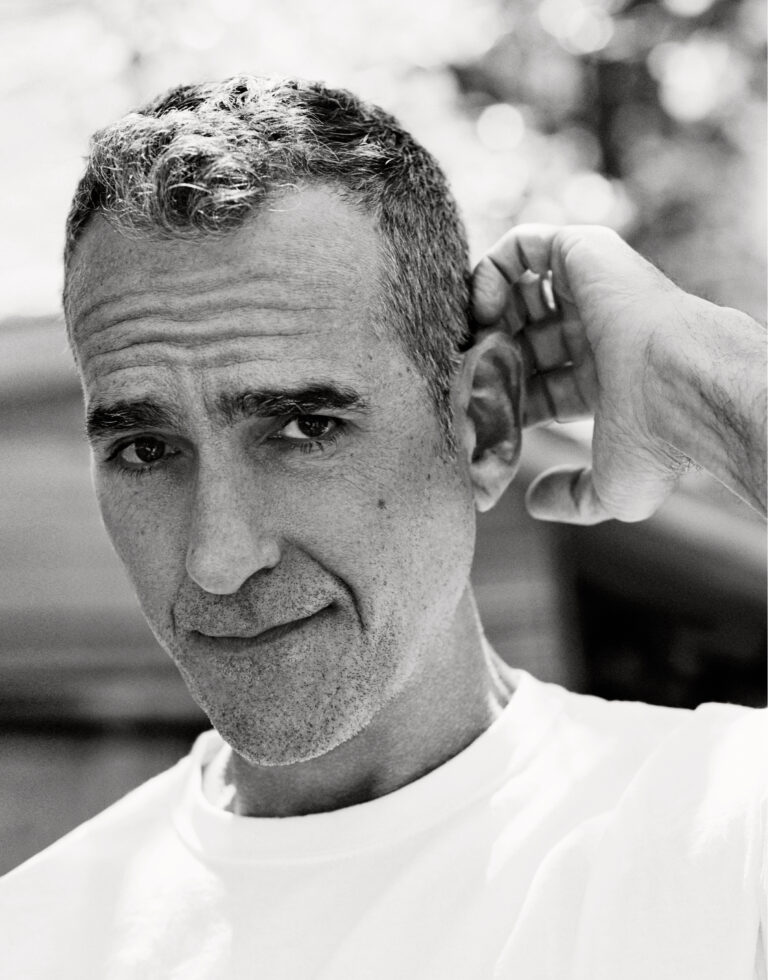

Bob Paris

The former Mr. Universe has swapped the heights of fame for an island life of poetic reflection

55-year old Bob Paris lives discreetly, in bucolic bliss, on a remote island. In 1983, however, the American-born sportsman reached the pinnacle of fame as Mr. Universe and the second most famous body builder in history. Now a poet and a Canadian, residing in British Columbia, he’s never managed to shake off his handsome looks, and has been a model muse to many prolific photographers.

Bob has also appeared on stage at Manhattan’s Carnegie Hall, worked as a fashion designer and written numerous autobiographical fitness and self-improvement books, including ‘Natural Fitness’, ‘Beyond Built’, ‘Prime’ and ‘Generation Queer’.

From Fantastic Man n° 22 — 2015

Text by WILLIAM VAN METER

Photography by BRUNO STAUB

The former Mr. American and Mr. Universe Bob Paris is a fraction of the size he was when he was a professional bodybuilder. The most famous practitioner of the sport after Arnold Schwarzenegger, the six-foot-tall 55-year-old is super fit and has notably sinewy arms, but he is now small enough to step inside his former body like it was an exoskeleton. I picture Sigourney Weaver in ‘Aliens’: “Get away from her, you bitch!”

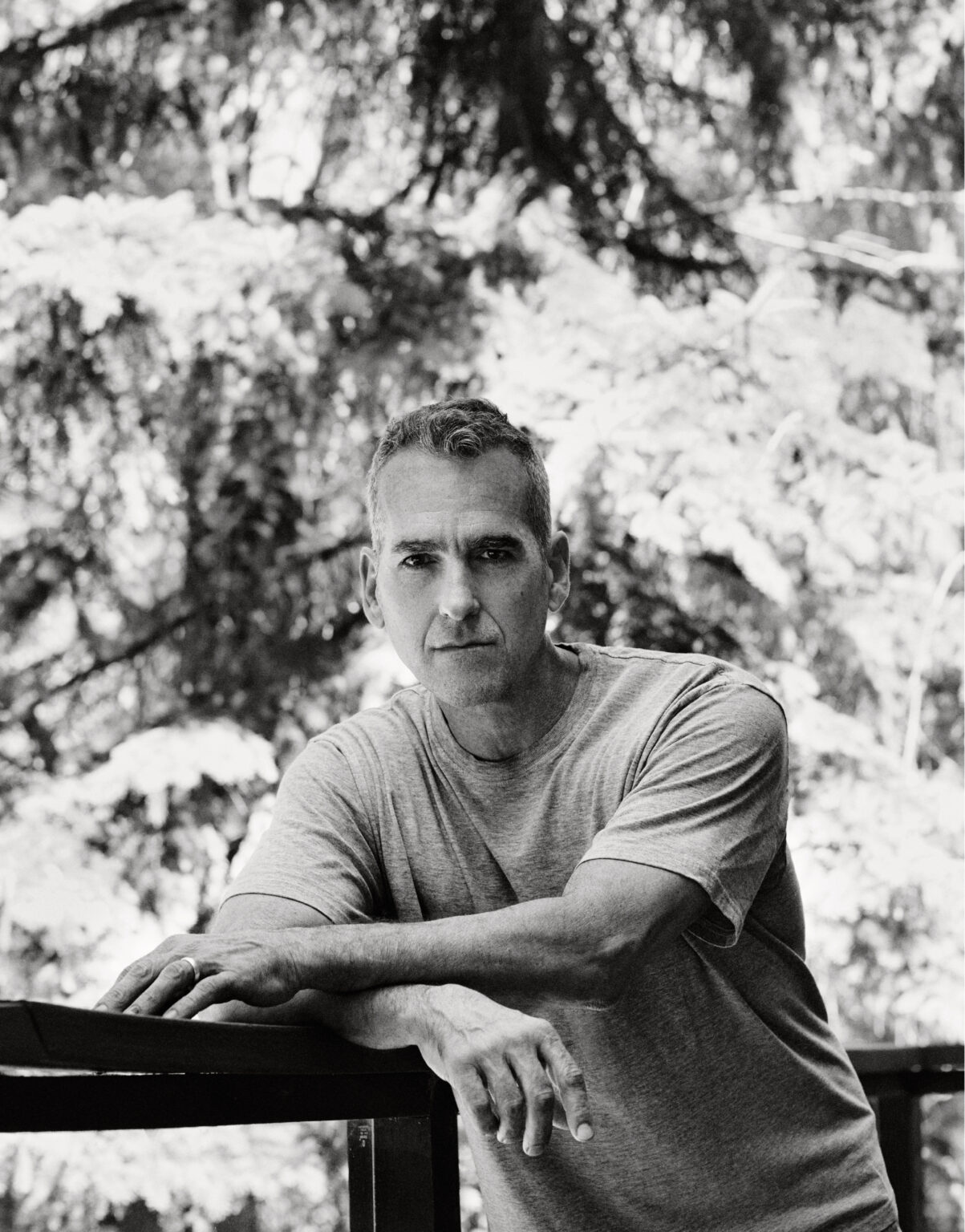

Barefoot in the yard of his cottage on Pender Island, in western Canada’s Gulf of Georgia, Bob is wearing a navy T-shirt paired with light-blue cargo shorts. His salt-and-pepper hair is slicked back, and he has on black-framed nerd glasses. He is strikingly handsome and strong-jawed and has a Zen demeanour. Accompanying him is his large and noisy black standard poodle, Cole. “He barks at the neighbours every time they walk up the driveway,” Bob says admiringly. “No one is ever going to sneak up on you, eh, Cole?”

Bob Paris is well aware of the stereotypes that go with his former sport, and he has made a career out of breaking all of them. Throughout his existence, the thread that has linked all iterations of his persona is that he transforms himself. He went from painfully shy teen to champion bodybuilder, pushing the limits of the human form. At the peak of his bodybuilding tenure, he became the first athlete to come out as homosexual while still competing in the sport. He’s been an outspoken critic of steroid use, an advocate for gay rights, a model, a fashion designer, a staple guest on a multitude of talk shows, an actor and a personal trainer. For a time, he had a very specific type of localised fame; then he was properly famous, and then famous for being famous. Now, he thinks he’s in his final incarnation, the one he was meant for all along.

“Bodybuilding was accidental,” he says. “I know that when my obituary is written, the bodybuilding stuff will be there front and centre, and I get that. But for me, it’s almost like it was an interruption from a path that I was supposed to be on. But I had to find bodybuilding, because without it, I would probably be dead.”

In the yard, Bob points out the different pear, cherry, apple and plum trees that surround his home. “It remains to be seen how much fruit we’ll get this year,” he says. “Since I was twelve, I had a fantasy of living in a house just like this out in the woods. I didn’t realise it was going to be in Canada.”

Inside, the house is an open space, with wood-planked floors and ceilings. A stained-glass sunflower hangs in the picture window, and coloured bottles line the sill. Framed family photos are scattered throughout – Bob’s brother stayed in their native Indiana and is a police officer – and above the green-painted brick fireplace is an oil painting of three regal dogs. Beside it is a large, glimmering silver bowl, which would look quite grand if it wasn’t filled with various remote controls.

It is the winner’s trophy from the 1982 Mr. Southern California contest, and it has formerly served as a pen holder and an outdoor birdbath. It’s the only visible totem of Bob’s former life, and he’s obviously not precious about it. “My husband, Brian, likes to polish things,” he says. “I like to let them go all worn and rugged-looking.”

The woodshed behind Bob’s house is dilapidated, its roof collapsed and sad. Brian is eager to repair it, but all construction on Pender has been banned due to the summer drought – the chance of forest fires is extreme, and any spark could ignite an inferno. Bob and Brian – Lefugey, an executive at a non-profit organisation – are both quite handy and remodelled their home themselves. Together since 1996, they married in 2003.

From Vancouver, one must take a two-hour ferry to another island and then get off and take another ferry to get to Pender Island, which has an area of 34 square kilometres and a population of about 2,250. The local students take a boat to another island to go to school. Pender is as isolated as it is overwhelmingly beautiful, a Canadian Eden with really bad food. A large resort occupies a tip of the island, built on top of a Native American burial ground, à la ‘Poltergeist’. There is a government-sponsored hitchhiking system in place: you can sit on a bench and wait for a friendly local to pick you up. “We’re not deeply integrated into the community here,” Bob says, “but I think that’s just my nature. Proportionately there’s a really big gay population. I think the lesbian community is bigger.”

Bob was born in 1959 in Columbus, Indiana (population 45,775), where everyone called him Bobby, and he started plotting leaving home when he was 10 years old. “This was right before my parents divorced for the second time and went their separate ways,” he says.

He lived with his father and was interested in books, art and theatre. In high school he played basketball and football. “I was this artistic kid that did sports because that was what was expected of boys,” he says.

“When I was a teenager I started to faintly come to grips with who I was. My sexuality began to enter into the picture, and I entered a very nihilistic stage of life.”

His father would kick him out of the house for minor infractions, like shoplifting a ‘National Lampoon’ magazine. “One time he threw me out in between junior and senior years because he found a bong in my car,” Bob says. “And he was a guy who would drink a bottle of J&B whiskey regularly. We were two alpha rams, butting heads and both partying a lot.”

It made Bob feel disposable, he says, so late one night, on a whiskey bender, he drove to a cornfield and loaded his shotgun. Weapon in hand, he strode across the field and sat against a maple tree, where he found a stick sturdy enough to push the trigger back; he couldn’t reach it with the barrel in his mouth. He woke up in the morning passed out underneath the tree, an empty liquor bottle and the shotgun beside him. “I guess I had thought, if I go through with this, how will I get to California to be a champion?”

By this point, Bob had discovered bodybuilding. One day at school, while on an errand for a teacher, he found an outdated weight machine hidden away in the gym basement. It was like he had found the pirate’s booty he didn’t know he had been searching for his whole life. He became one with the machine, its straps and pulleys forming an extension of his body. The physical effects were rapid. This was the ’70s, when weightlifting wasn’t de rigueur for teenage boys, so his passion made him stand out even more than he thought he already did.

“After I’d been training a little while, I went to a newsstand to buy a backpacking magazine,” he says, “and there was this copy of ‘Muscle Builder’ magazine with Arnold Schwarzenegger on the cover. A bell sort of went off. I was at this transitional stage in my life where it could’ve gone either way. I grabbed it, and it just seemed to give me this focus. Me and my friends played sports, but we partied hard, and this thing just began to veer me away from that path and give me something to really focus on.”

If there was a sexual element to his interest, it was deeply sublimated. “The magazines in those days were very informative. It was about learning this craft.”

Bob went to college, where he majored in English, but he swiftly dropped out to immerse himself in training and dedicate his life to his dream of being a bodybuilder. He briefly moved to Florida to live with his grandparents and entered his first contest, for which his grandmother sewed his first pair of posing trunks. He moved to California to be part of Venice’s Muscle Beach scene, the focal point of the bodybuilding world, and began his swift ascent, winning amateur contests like Mr. Los Angeles in 1981 and turning pro in 1984. With his chiselled features and made-for-Hollywood hair, Paris became a popular cover star of the magazines he once so avidly collected. He appeared in ads for workout wear and protein powder.

It was a time of never-ending diets and workouts. “I took a Zen approach to it,” he says. “I saw the training as being as much about my human growth as it was about what I was trying to sculpt.” The form he created was superhuman, showing an extremity of dedication akin to that of body modification artists like Orlan. Paris’s posing is, in fact, an art unto itself, an entrancing Salome-like performance, a choreographed dance with every muscle in his body flexed for the entirety. Many of his performances are catalogued on YouTube and are well worth viewing.

Bob celebrated his 21st birthday by going to a gay bar, and he views that venture as the moment when he came out to himself. He immediately became serially monogamous; there were no secret salacious group rendezvous with closeted bodybuilders (I asked). Very quickly, everyone in his personal and sporting life knew he was gay. But though his manager and the other bodybuilders knew, the issue was sidestepped when it came to his public persona. When he was interviewed for a magazine, he never made up some tall tale about a girlfriend, but it was agreed that it was in everyone’s best interest if his homosexuality wasn’t broadcast. He was huge within his sport, but besides Schwarzenegger, no one in it had made a full crossover to pop culture, and those around Bob considered the stakes just too high.

In the bodybuilding world, there’s always someone around the corner with a better body. The problems of professional bodybuilders aren’t necessarily what one might expect, given the he-man image they project. Their world has an aspect more often associated with teenage girls – it’s rife with gossip, body dysmorphia and eating disorders. Bob recalls feeling deep shame when, as an adult man, he was laughed at by a group of teen girls in a restaurant. “I felt very self-conscious all of the time,” he says. “In a very simplistic way you could say, ‘Well, you’re focusing on yourself so much.’ There’s a narcissism in that. One of the frustrations that I had was that when a Major League Baseball player finishes a game, he leaves his mitt behind in the locker room, takes off his uniform and goes off into a normal life. I was always frustrated with the aspect that I couldn’t remove the gorilla suit and leave it behind and have this normal life.”

Bodybuilders are paradigms of fitness, but they have issues that mirror those faced by the morbidly obese. Coach seats on planes are out of the question, and movement is hard when you have so much bulk.

“Clothes didn’t fit right,” Bob says. “That was really frustrating. I couldn’t fit into jeans in those days, when I had huge legs. I’d have to buy 501’s with a 40-inch waist and then have it cinched, and the legs would still be really tight. And as for shirts, nobody was making XXL in those days.”

As a solution, he parlayed his fame into his own clothing line, Bob Paris Fashions, which he founded in 1982. Mostly a mail-order business, it featured a lot of “V-neck sweaters that were synthetic but felt like cashmere.”

He doesn’t have any items from the Bob Paris Fashion years saved, but they’re certainly worth an eBay search. “I might have a tear sheet from one of the ads,” he says. “That stuff’s all buried away.”

By 1984, Bob Paris Fashions became overwhelming to balance with his athletic career, and he shut it down. “I just wasn’t feeling the vibe,” he says, “and that was the point where other pro bodybuilders took a cue and started doing their own lines, mostly with what I call Koko the Clown pants, those crazy-patterned high-waist sweatpants from that era.” As the fashion business wrapped up, Bob became increasingly aware of the ephemeral aspect of his sport.

“Bodybuilding is an exercise in temporary condition,” he says. “It was like being one of the sand sculptures that the Buddhist monks make. They go through all of this to put this sculpture together, and then it just gets swept away. Every single time you get yourself into a condition, it lasts for a very finite amount of time. And then it’s just: begin again.”

He began to perceive a shift towards a freak-show aesthetic – this was the height of steroid use, and the veinier and more orange you could get, the better – and in 1985, he retired from the sport.

“It was a relief for me,” he says. The burden of his unusual physique and regimented lifestyle was lifted. He went back to his childhood passion: the theatre. He did a two-year course at the renowned Stella Adler Studio of Acting. He limited his exercise to jogging and slimmed down to a size more natural for his frame. He performed in student productions of ‘The Glass Menagerie’ and ‘Mass Appeal’.

“Those two years were the happiest period of that decade of my life,” he says. “When I threw myself into training, I left that part of my life behind, and suddenly I felt like I had found it again. I was fulfilled. I was hanging out with interesting people, actors and directors and writers, so different to my sports friends. It was like theatre group in high school all over again.”

He took up traditional modelling, too, shooting with photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe (his portrait would appear in the monograph ‘Certain People’), Herb Ritts for ‘Interview’, and Bruce Weber for ‘GQ’ and ‘L’Uomo Vogue’.

“I’ve been looking at pictures of Bob Paris for years and wishing that I had his body,” says Weber. “When I photographed him, he assured me that if I went into training alongside of him it wouldn’t be hard. Bob’s a real gent, and he’s been a help to so many people, encouraging them to stay healthy and have confidence in themselves no matter what size. His nature is gentle, and his muscles are powerful.”

Bob’s looks were definitive of the 1980s Western male beauty construct. It is evident that he could have had a wildly successful career as a model, but it was a path he wasn’t interested in. He had his sights set on Hollywood. Sadly, after finishing acting school, he discovered a hard truth about being gay in the movies in the ’80s: Hollywood didn’t have its sights set on him. “To be a leading-man type and be living an out life – that made a movie career impossible,” he says. “It may have been possible in New York theatre, but I didn’t even think in those terms. So I panicked, and I went back to training.”

In a gym in Colorado, he met Rod Jackson. After a very brief courtship, they were “married” in a Unitarian ceremony. Gay marriage wasn’t yet legal, so the commitment ritual was symbolic.

In the July 1989 issue of ‘Iron Man’ magazine, Bob told an interviewer: “I’m gay. However, my burden is not my gayness but that I was raised by my family and by society to hate myself for being gay. I grew up being taught to dislike the person I really was. It was a very difficult cycle to break out of. Basically, the point that I’m at in my life now is that I’ve developed a level of pride and a level of honesty and a level of self-assurance.” He then detailed his relationship with Rod and said, “I want people to realise I am a gay, married man, and I guess there will be people out there who won’t like my physique any more because I’m gay. That makes me laugh. What does my gayness have to do with my physique?”

Bob Paris and Rod Jackson simply became “Bob and Rod,” the Kim and Kanye of the era: a smiling, ripped advertisement for wholesome gay monogamy and a buoy of hope floating atop the depths of the Aids crisis. The couple appeared on a score of talk shows, including ‘Oprah’, espousing marriage equality. They were a constant on the covers of gay publications such as ‘Genre’, ‘The Advocate’ and ‘Out’, for which they emulated Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’ painting, standing in front of a barn clutching a pitchfork. They walked holding hands in skimpy swimsuits for Thierry Mugler’s AMFAR-benefit fashion show (other models included Dolph Lundgren and Jeff Stryker).

“I remember being on a kind of gay celebrity cruise around Manhattan in the ’90s,” says the writer and biographer Brad Gooch, “and the celebrity of celebrities was the duo Bob and Rod. They were wish fulfilment for gays. Their body type was the new ideal, a redefinition of gay identity in its own way. If Mark Spitz was the athlete pin-up for gays in the ’70s, Bob Paris was it for the ’90s – and actually out and gay. I always wondered how much awareness of Aids helped muscle-building blow up. Instead of actual sex, we had visual, aesthetic, kind of untouchable marble statues to aspire to – that was quintessentially Bob Paris.”

If the gay community was fraught with strife and in the midst of a plague, the look of perfection could at least be achieved. ‘The Advocate’ wrote about Bob and Rod: “Strong, handsome and committed, the two seemed to satisfy the growing hunger for an attractive image of gay love in the age of Aids. For a public that was increasingly bombarded with images of the gaunt and frail, Jackson and Paris were a godsend.”

Bob retired permanently from bodybuilding in 1991. He felt that his coming out had added bias to the already subjective criteria of judging, and he was entirely disillusioned with the sport. “I started to realise I was fighting for the wrong things,” he says. “I’m fighting for a situation where I might as well be getting up in the morning and going off to the coat hanger factory. It would be just about business, it wouldn’t be about passion.”

But Bob and Rod were in-demand public speakers. They founded the non-profit Be True to Yourself Foundation, which raised money for gay youth outreach groups. Bob published ‘Beyond Built’, a 1990s equivalent to Charles Hix’s book ‘Looking Good’ that combined a workout how-to (he is depicted doing the “sissy squat” with Rod) with tips on diet and grooming. In 1991, Herb Ritts published ‘Duo’, a hardcover photography book featuring the pair nude. Their bodies were rendered as landscapes, extensions of the beach settings that were more sculptural than sexual, and shot in black and white – a boon in that it camouflaged Rod’s bright yellow First Lady hair. They were the kissing sailors in David LaChappelle’s controversial Diesel ad photo, originally shot for a ‘Details’ article (which was dropped due to fears it would scare away advertisers) about the book ‘Straight from the Heart: A Love Story’, by Rod and Bob Jackson-Paris. It was a rote, saccharine history of the couple, who by that point had hyphenated their last names, and their supposedly perfect relationship.

“It was a book written by committee, aimed at people who don’t read,“ Bob says, sitting outside at the patio table on his deck. One would assume that with all this fame, glory and fabulousness, the period of his life spent with Rod would have been a zenith in Bob’s life. He thinks of it very differently. He shows great consternation when asked about it, and during the conversation he will not even utter his former partner’s name. “I have,” he says, and pauses, his words measured and cautious, “mixed memories about that period. I want to be careful how I say… I wanted to come out in the media, because I was living out, and then just go back to work, but I was with someone who wanted to turn that story into a couples story. Because I was young and in love, I went along with it, and it took on a life of its own and ended pretty badly.”

By 1994, Bob and Rod were living in separate parts of the house. They split in 1995. Rumours swirled, and in 1996, Bob faxed out a press release. It read in part: “While our marriage was lived in the public eye for many years, its demise is not a subject either of us can expand upon in the media.” It was like the Gwyneth Paltrow-Chris Martin “conscious uncoupling” – the splitting of this ideal, self-satisfied couple was cathartic for those whose lives weren’t as impossibly perfect. But it was also a blow for the gay cognoscenti, who saw them as ambassadors for the cause, making gay marriage palatable instead of science fiction and simply living as an out gay couple in an almost uninhabited playing field.

“It felt like the hardest, most humiliating thing I’d ever been through,” Bob says. “He walked away and left me with the entire mess to clean up. The mainstream press was brutal. The gay press was really brutal. One of the great blessings was that social media and the internet didn’t exist then.”

On Pender Island, Bob is walking through a patch of sawgrass that’s brown and scorched from the drought and strong sun. He gets to a bluff on the south-eastern tip of the island, just above the dark, rocky beach. It is strewn with driftwood, and someone has built a small hut with pieces of it. On the right there is an expansive, lush forest.

Ahead is a majestic view of the calm waters of the Strait of Georgia. “I try to see it with fresh eyes each time,” he says, “and never lose that sense of awe.” Other islands are visible in the distance; most are part of Canada’s territory, but Orcas Island (the water is teeming with the whales) is also in view.

Orcas Island is part of the state of Washington, and it is where Bob retreated after ending his first marriage. He went from being judged and viewed onstage as a bodybuilder to the harsh realities of wider fame, and he wound up removing himself from the public gaze altogether. He lived alone in a cabin in the woods, acted in community theatre and wrote a memoir, ‘Gorilla Suit’ (it was published in 1997 and is now out of print). It focuses on his experiences in bodybuilding and doesn’t explore the white-hot fame bubble he had freshly exited.

Today, he and Brian are going to take the dog swimming just before sundown. The two met in Palm Springs, California, in 1996. “I’d sworn to myself I was never going to be in a relationship again,” he says. “I would just find sex when I needed it. I’d use my imagination. I was going to be content to be on my own. I’d just go back to the island and write and be happy.” But Bob and Brian ended up with feelings for each other. “It’s going to sound weird,” Bob says, “but I remember walking into a Denny’s on our first date, and I thought, ‘I’m walking in with my husband.’” Soon after, Brian moved to Washington to live with him.

Brian had a long history of cancer (he’s now in remission), and they moved to eastern Canada in 2003 when his health was deteriorating. “We didn’t know which way his battle was going to turn out,” Bob says, “and he wanted to live near his folks.” They married soon after their arrival, and Bob is now a Canadian citizen. They moved to Pender Island nine years ago, and Bob has devoted himself to writing since. He’s been writing poetry since his bodybuilding days and posts some of it on his website.

“There’s a disconnection between life then and life now,” he says. “My life before Brian was like this weird little tunnel I had to go through. My life has moved in a much more authentic direction – much more how I would’ve predicted it to turn out.”

He continues, “I always [have] wanderlust. There’s always been a journey aspect to what I was doing.” He now seems to have arrived at the place he’s been searching for.

He squints out at the black rocks jutting from the water, the waves crashing upon them. “There are usually seals,” he says, “but I think it’s too hot out for them.”